|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

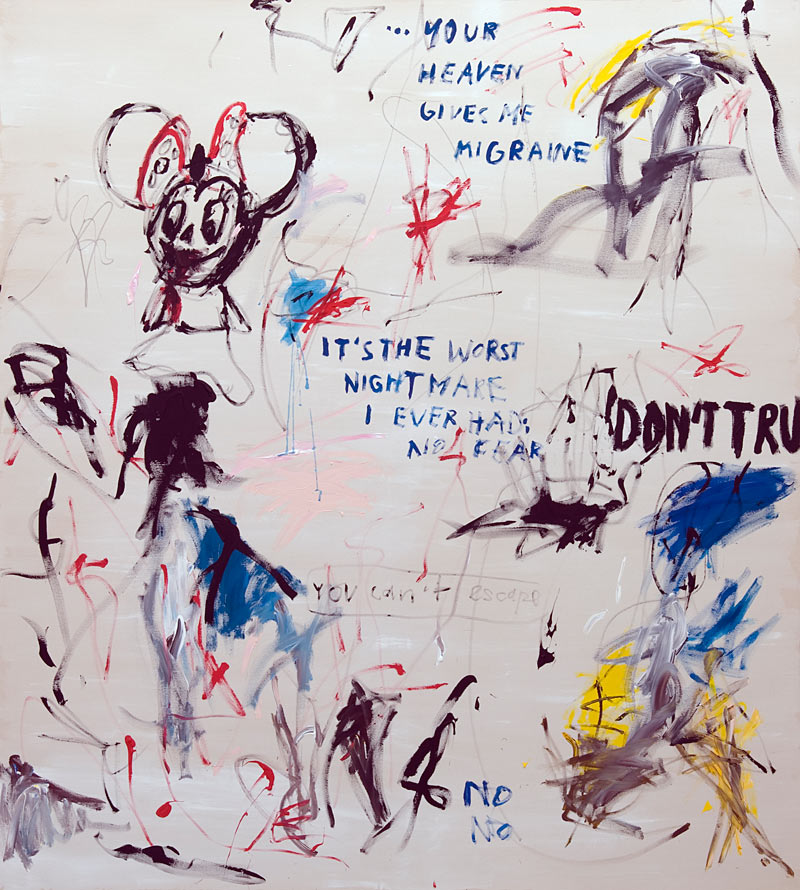

Cordula Ditz adopts principles of Appropriation Art. Each of her exhibitions is built up as a complete artistic system, a distinctive composition, made of loops, words, images and sounds. Furthermore, their juxtaposition, as an apparently constructed parody, is based on a precise and clear demonstration of structures.Her installations include found footage video works, paintings, and industrial materials, such as neon. The paintings, with their striking appearance and repetitive formal qualities, complete the system of art history references. Together with colored light and merging sound fragments, her work creates a complex display of images, words and sounds, unmistakably competing for attention.

The film material originates from horror movies of the 70s and 80s, a genre Ditz is focused on, precisely researching and studying the uncanny. Within the course of repetition, that the artist arranges, the horror loses its impact and the principal of a serial pattern shifts into the foreground. The demonstratively hard cuts simultaneously reveal the constructedness of the selected film material and the artistic appropriation itself as an analytical procedure. Lost in the void of an endless loop, the actresses begin to stylize themselves into a pose and their actions into choreographies of ineffective gestures. The removal of narrative content leads to an illustration of the structural system. In this way, decontextualised elements of the horror-film genre, which is based on conventional symbols and image categories, can be viewed in isolation from their linear cohesion. Also, this makes the images being discharged from their original content. Now, free for a new implementation, a work like the one of Bas Jan Ader ( I'm Too Sad to Tell You, 1970) finds its new frame inside a foreign source.

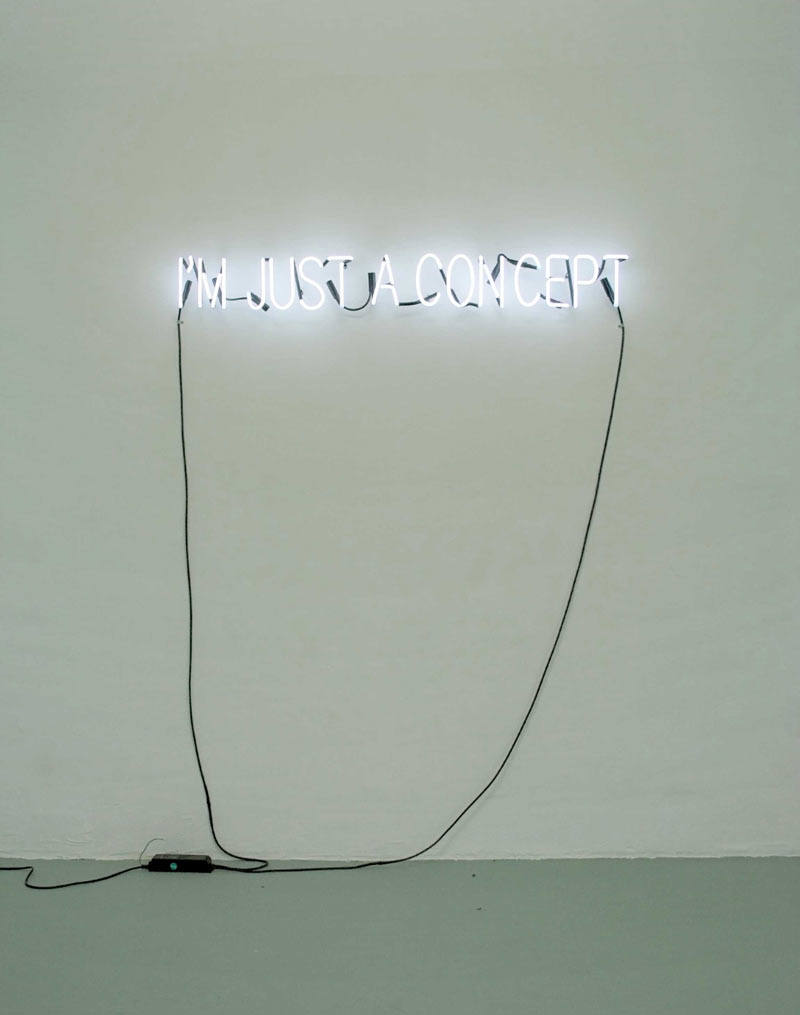

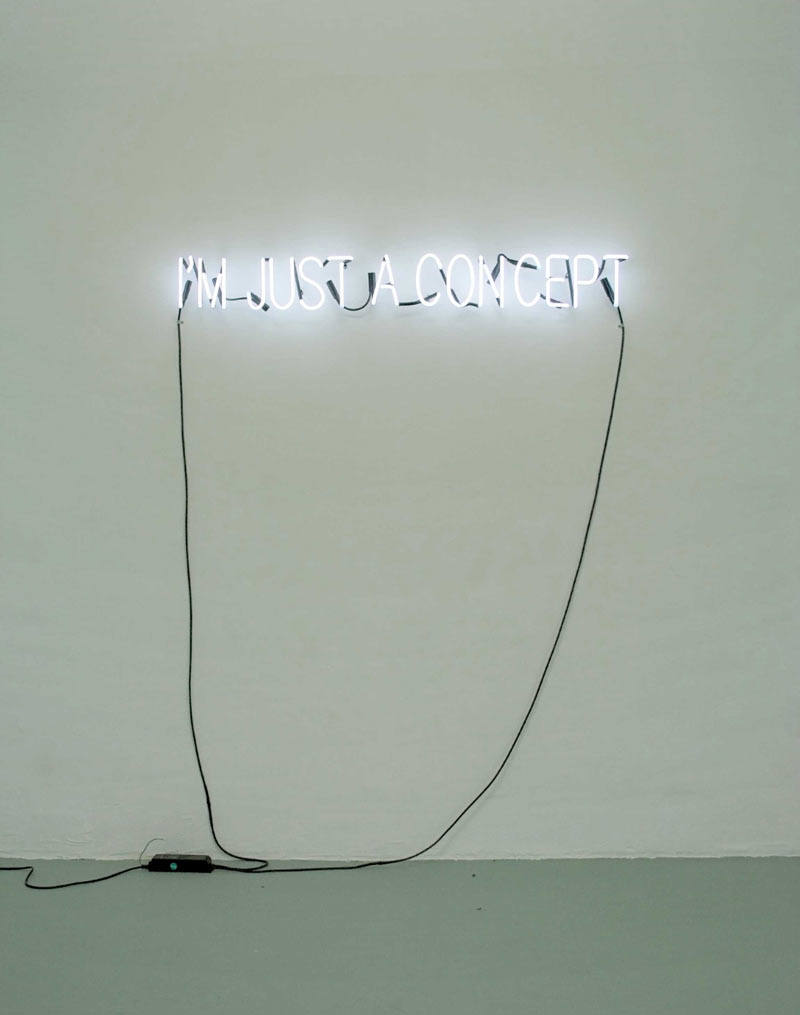

I'M JUST A CONCEPT: MEDIA, EMOTION, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY

In her 2011 exhibition I’M JUST A CONCEPT, Cordula Ditz examines the fluidity of identity and its mediation through images, narra- tives, and collective memory. Combining found footage videos, paintings, neon text works, and sculptural elements, Ditz constructs an immersive environment where repetition, fragmentation, and appropriation destabilize familiar representations, exposing the artificial nature of both cinematic and personal identity. The exhibition’s title itself suggests an inherent instability—a reflection on how the self is shaped by external forces, particularly media-driven emotions and archetypes.

At the core of the exhibition are two video works: CHARLOTTE – I’M TOO SAD TO TELL YOU and ELSA – I’M TOO SAD TO TELL YOU (both 2011). Each features a brief, looped sequence of a woman in extreme emotional distress, crying uncontrollably—a moment extracted from two obscure 1970s horror films. Charlotte draws from THE FORGOTTEN (1973), while Elsa originates from LA MANSIÓN DE LA NIEBLA (MURDER MANSION, 1972). By isolating and looping these short, raw displays of emotion, Ditz transforms these cinematic breakdowns into absurd, almost mechanical performances of sadness. The endless repetition drains them of their original dramatic weight, reducing these intense moments to patterns of movement and sound—gestures of despair that become unsettlingly formalized.

The title of both works references Bas Jan Ader’s I’M TOO SAD TO TELL YOU (1971), a conceptual piece in which the Dutch artist filmed himself crying, refusing to disclose the source of his sorrow. Much like Ader, Ditz foregrounds the performativity of emotion, questioning whether these cinematic moments of breakdown are spontaneous, real, or purely constructed. The isolation of the crying women from their respective narratives emphasizes their exploitation as emotional spectacle—a common trope in horror films, where women’s suffering often serves as a dramatic and aestheticized climax.

Directly accompanying the video works are two neon pieces that amplify the exhibition’s interrogation of media and selfhood. One spells out Fake in glowing red neon, a stark, immediate declaration that calls into question both the authenticity of cinematic emotion and the constructed nature of identity itself. The other, I’M JUST A CONCEPT, reiterates the exhibition’s title in luminous tubing, further reinforcing the idea of the self as a media-constructed illusion. The placement of these neons next to the crying women creates an unsettling juxtaposition—the glowing, commercialized aesthetics of signage set against raw emotional excess. This contrast highlights the collision of personal feeling with cultural expectation, where emotions are not only performed but also commodified.

The lower floor of the exhibition expands on these themes through a play with Minimalist aesthetics and horror film references. A flickering neon fixture, titled UNTITLED (TO LAURIE STRODE), pays homage to Dan Flavin—one of the pioneers of Minimalist light art— yet deliberately undermines his emphasis on precision and purity. Instead of the clean, stable glow of Flavin’s industrial materials, Ditz intentionally installs the neon tubes with faulty starters, causing them to flicker erratically as if they were malfunctioning. This deliberate imperfection transforms the work from a pristine light sculpture into something unstable and eerie, mirroring the anxiety-ridden atmo- sphere of horror cinema. The reference to Laurie Strode—the protagonist of HALLOWEEN (1978)—further grounds the piece in Ditz’s broader engagement with gender and fear.

The flickering, unstable light echoes the suspense and uncertainty of classic slasher films, where dimming bulbs and faulty fixtures often foreshadow impending danger.

Another sculptural element introduces a playful yet unsettling bodily presence into the exhibition space. In one corner, a mannequin stands with its back to the viewer, dressed in a blonde wig, red high heels, and a light pink mini dress—an unmistakable stereotypical outfit of a horror movie victim. The work, titled SCHÄM DICH (Shame on You), references Martin Kippenberger’s iconic self-pun- ishing sculpture MARTIN, AB IN DIE ECKE UND SCHÄM DICH (Martin, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself). By feminizing this act of shame, Ditz recontextu- alizes Kippenberger’s self-critique, directing it instead toward the reductive and formulaic depictions of women in horror cinema.

Rather than an artist’s self-inflicted shame, SCHÄM DICH turns the accusation outward, toward the viewer, the genre, and perhaps even the broader cultural machine that continually replays these tropes. The mannequin, frozen in its passive stance, becomes a stand-in for the nameless female characters whose scripted victimhood is repeated across decades of film history. Yet, by turning its back on the audience, it also refuses to perform—denying the viewer a clear gaze and challenging their role in consuming these images.

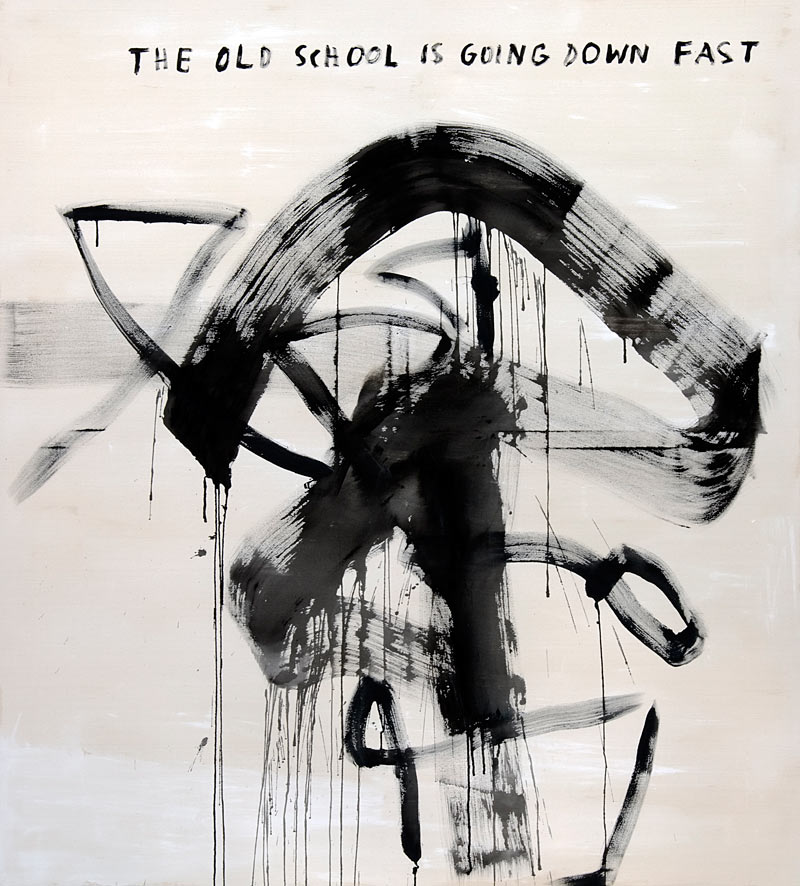

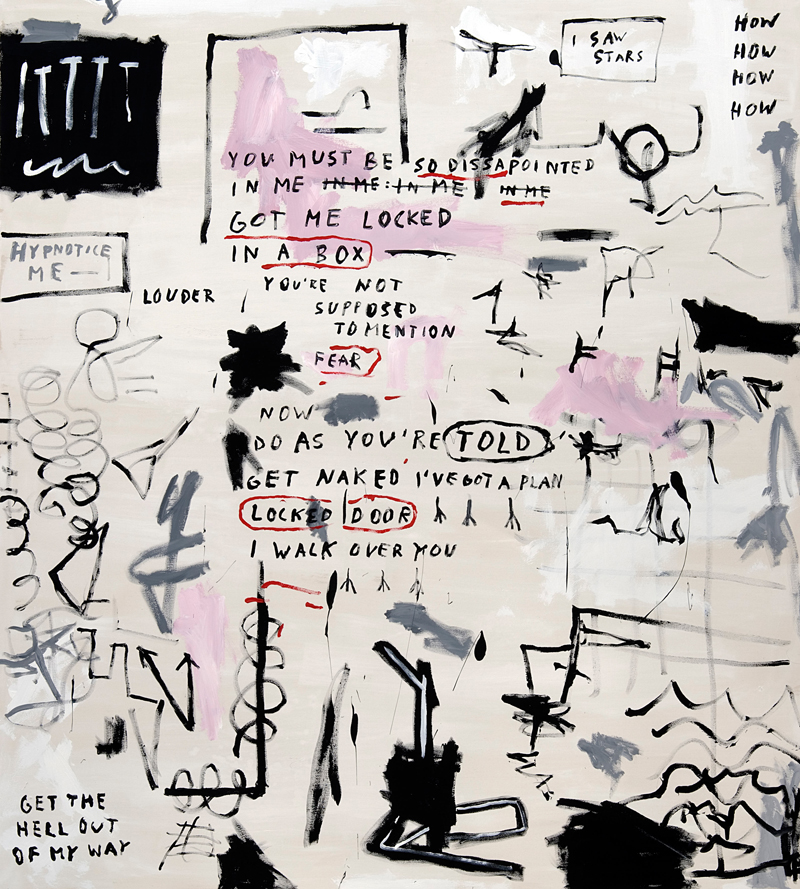

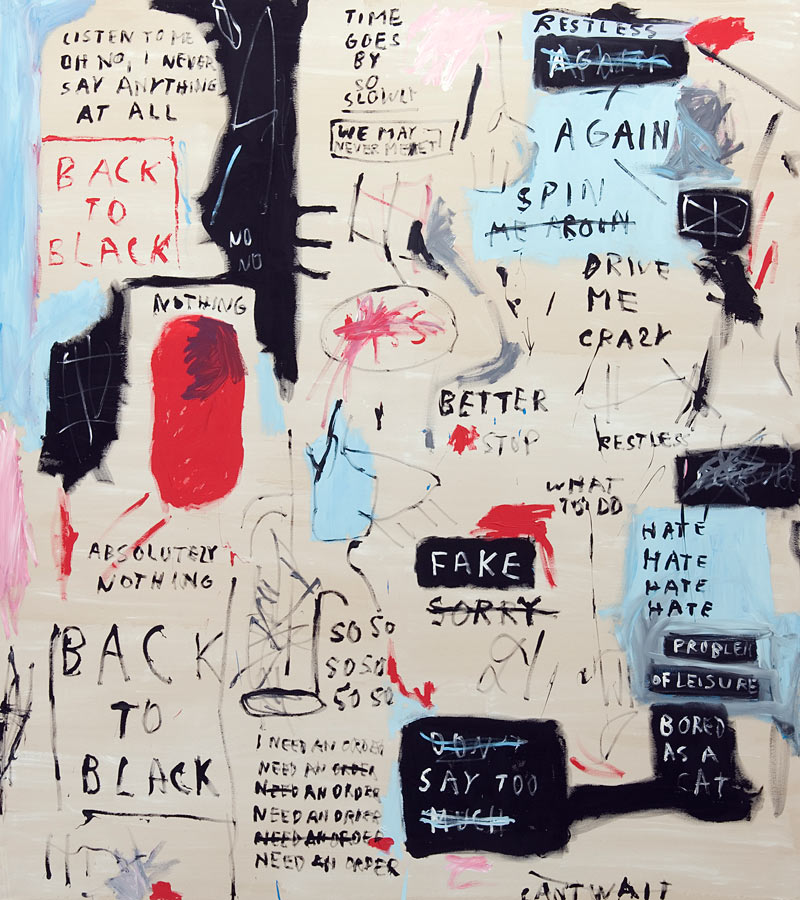

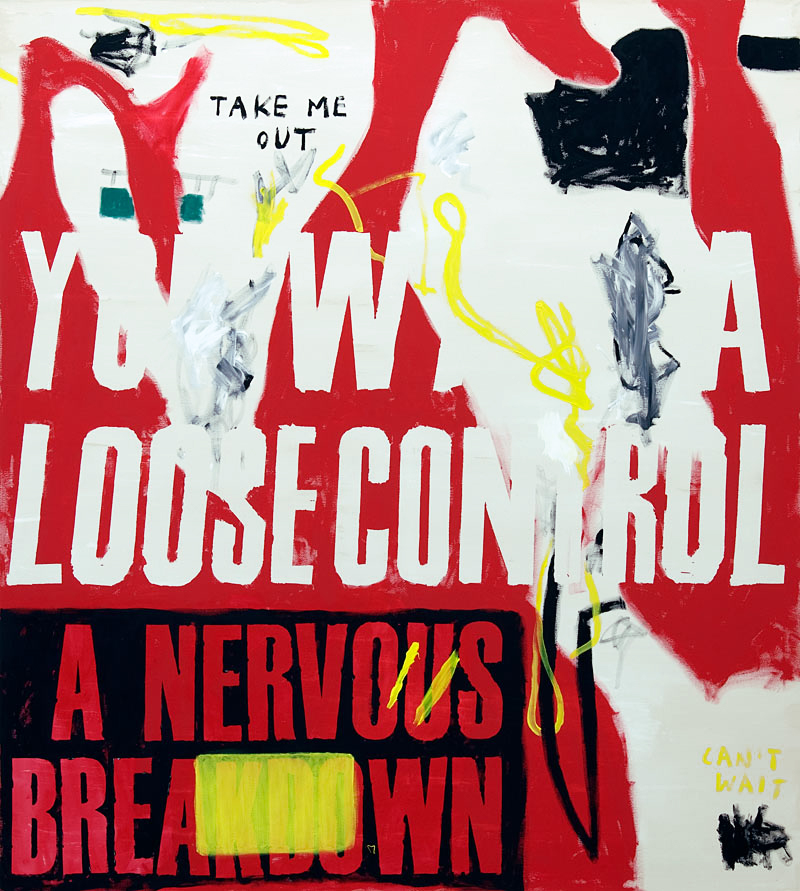

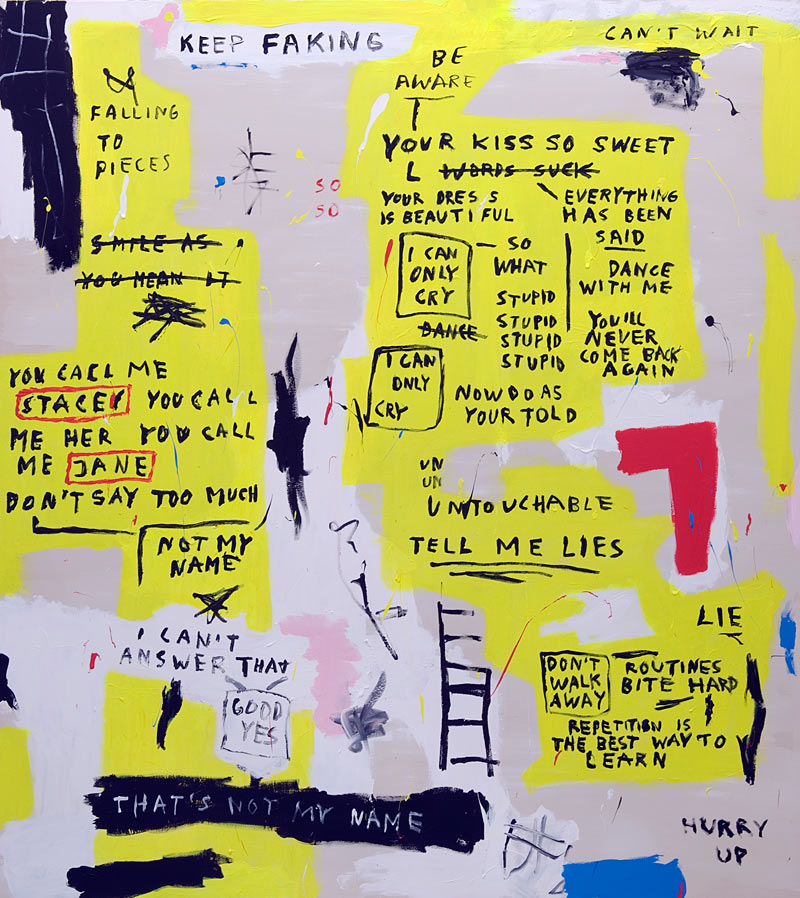

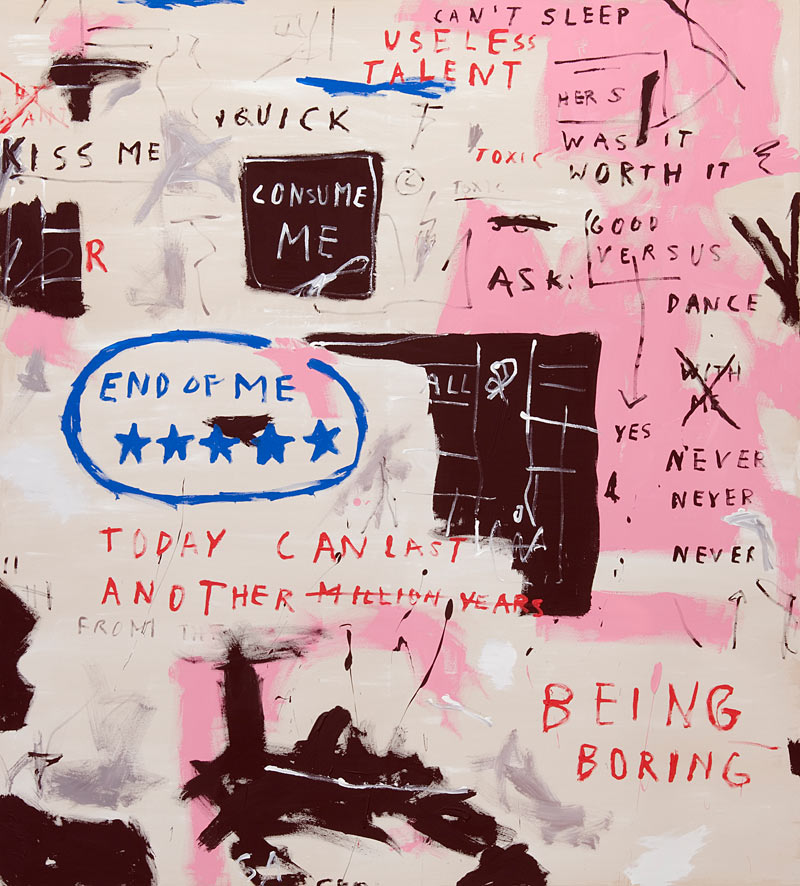

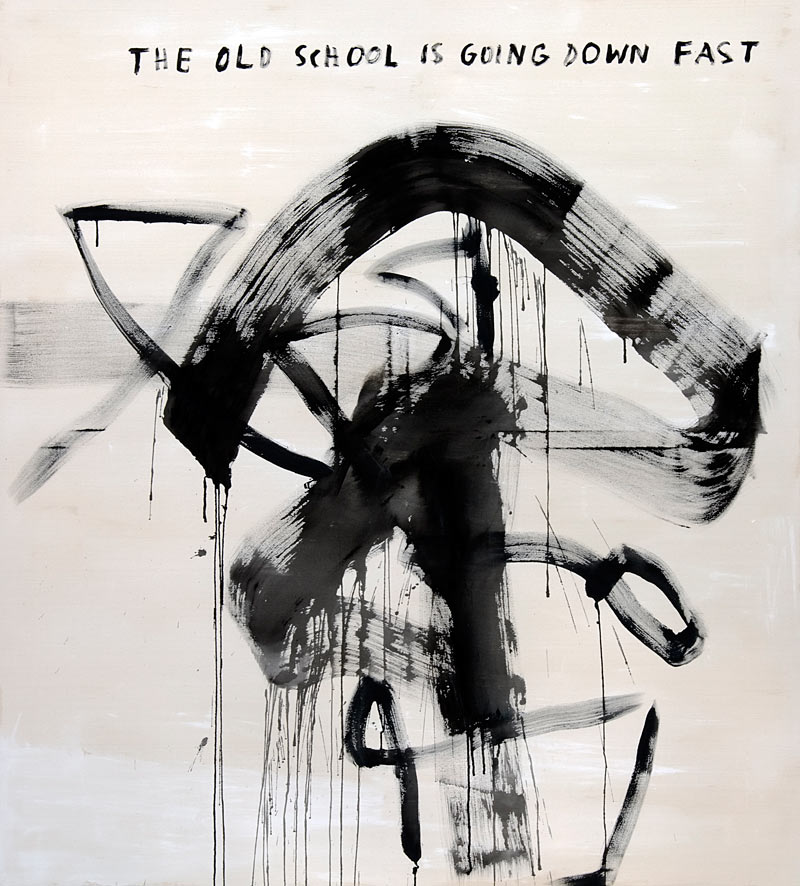

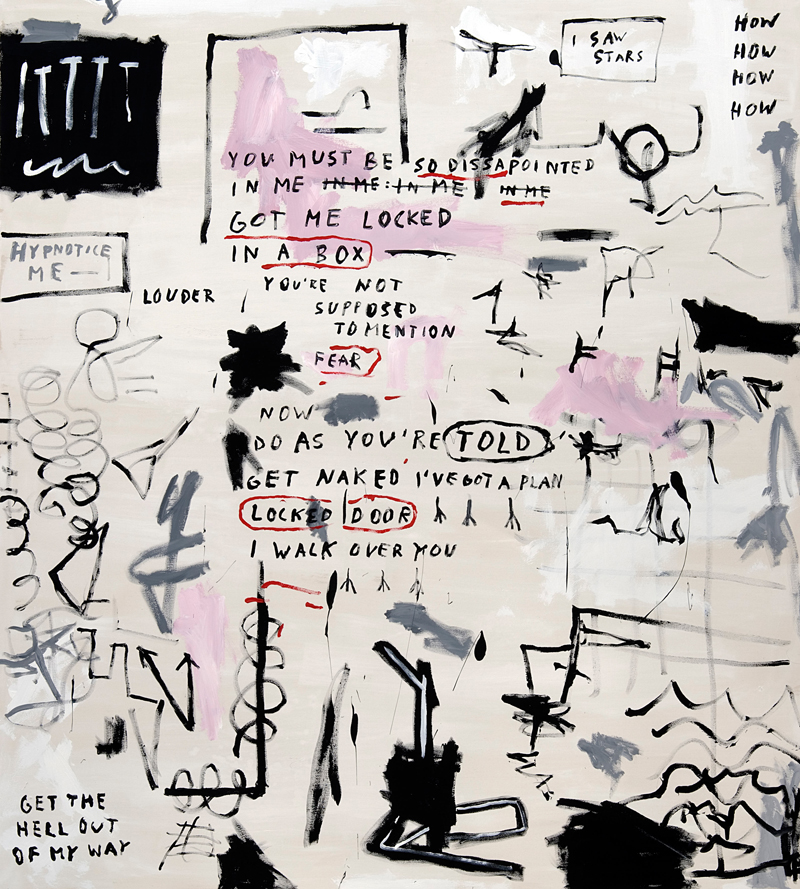

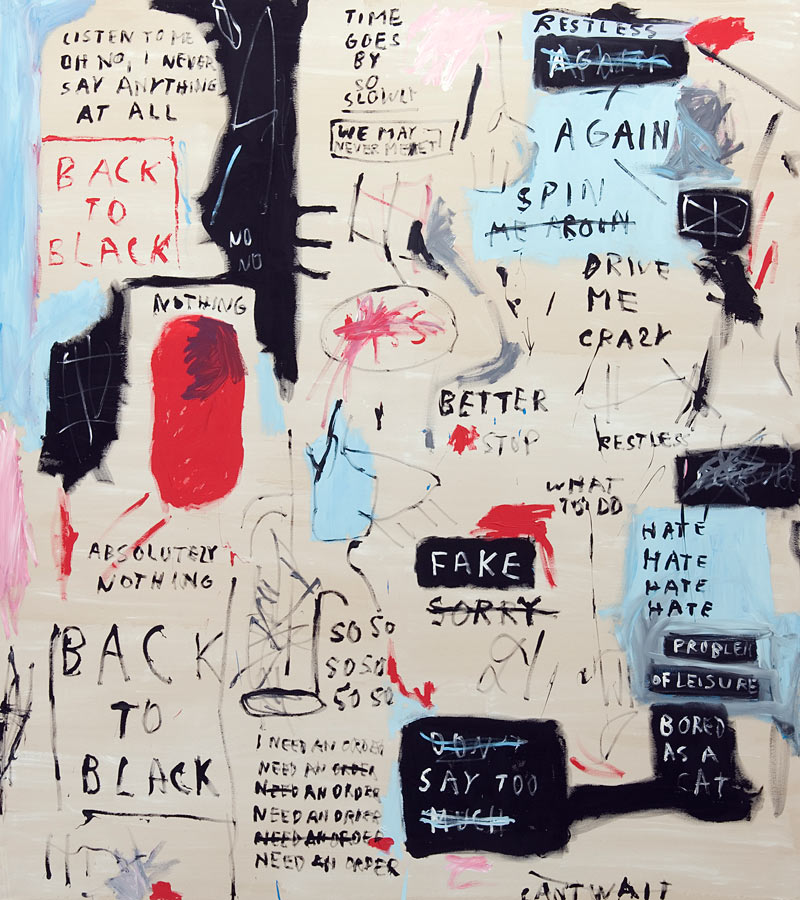

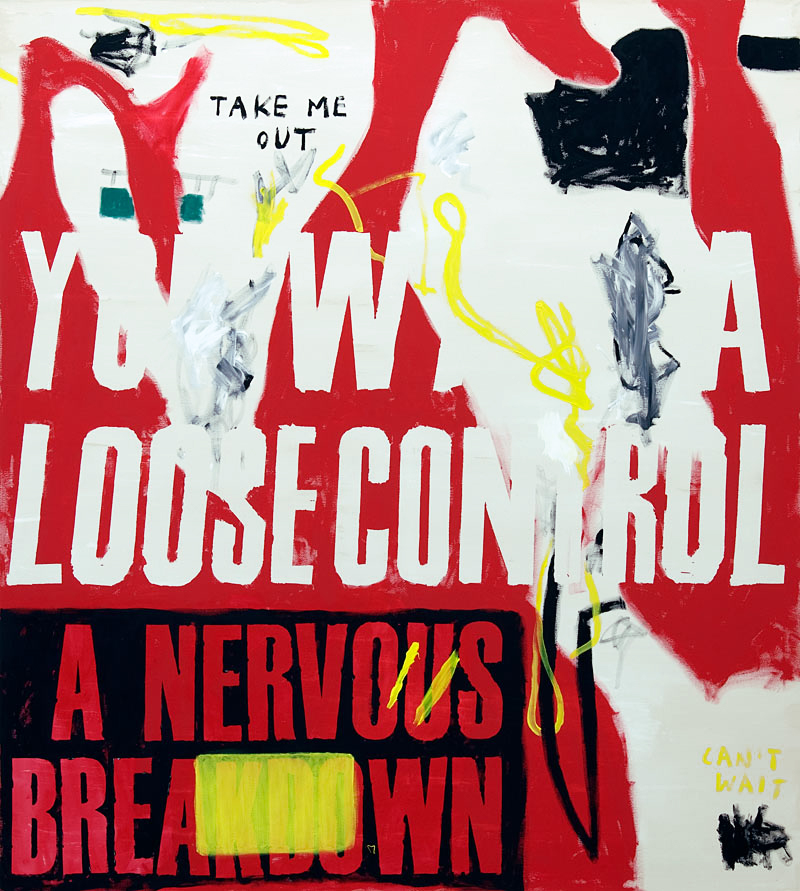

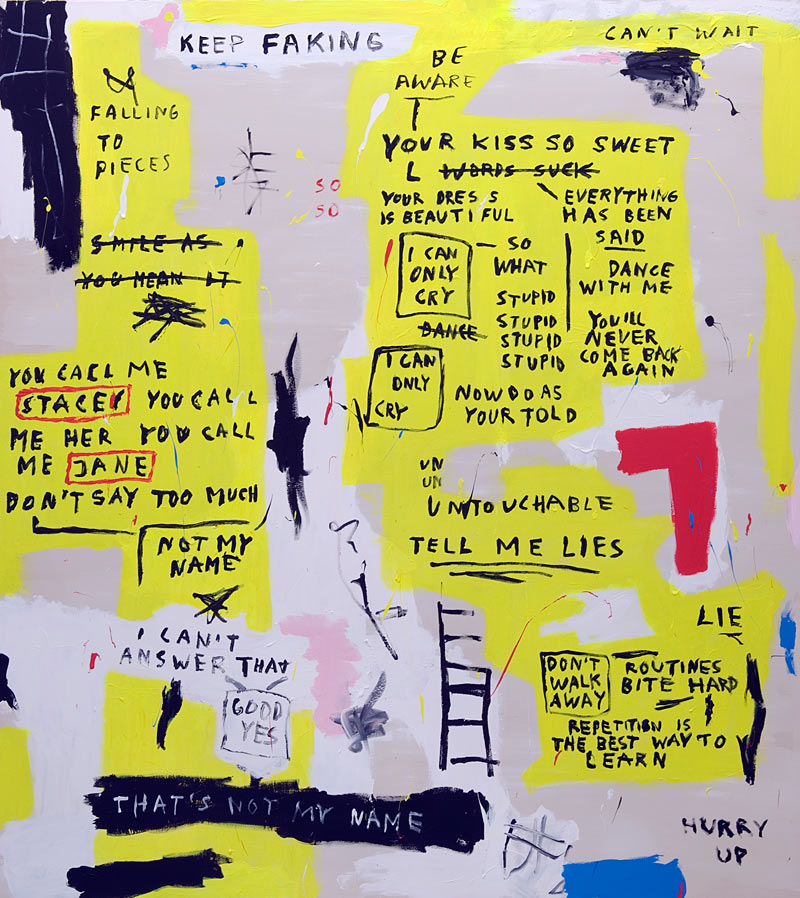

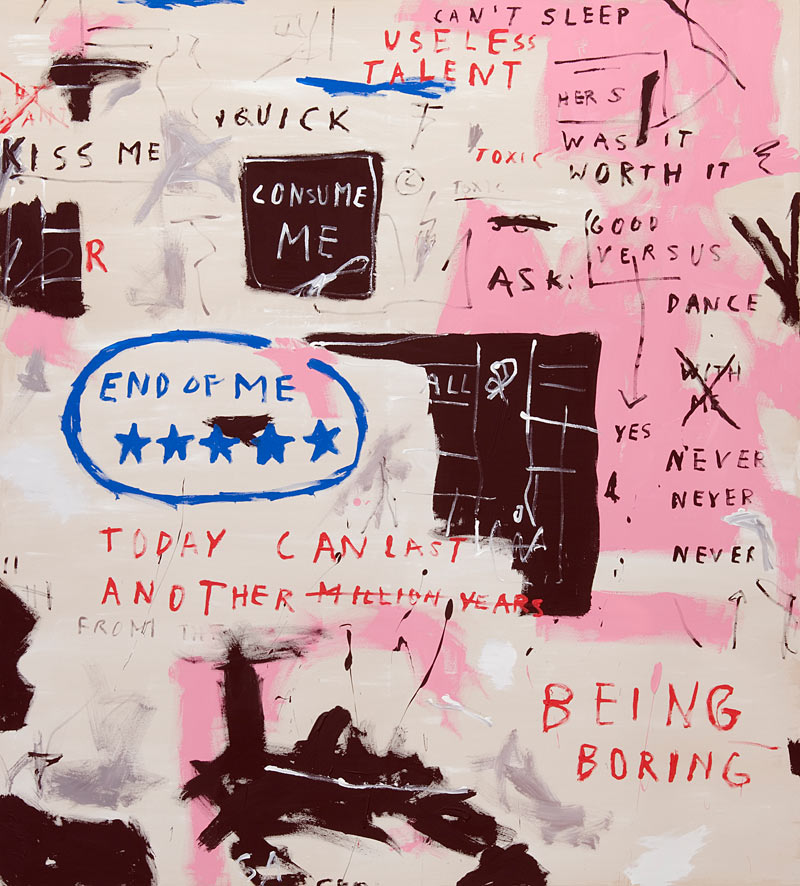

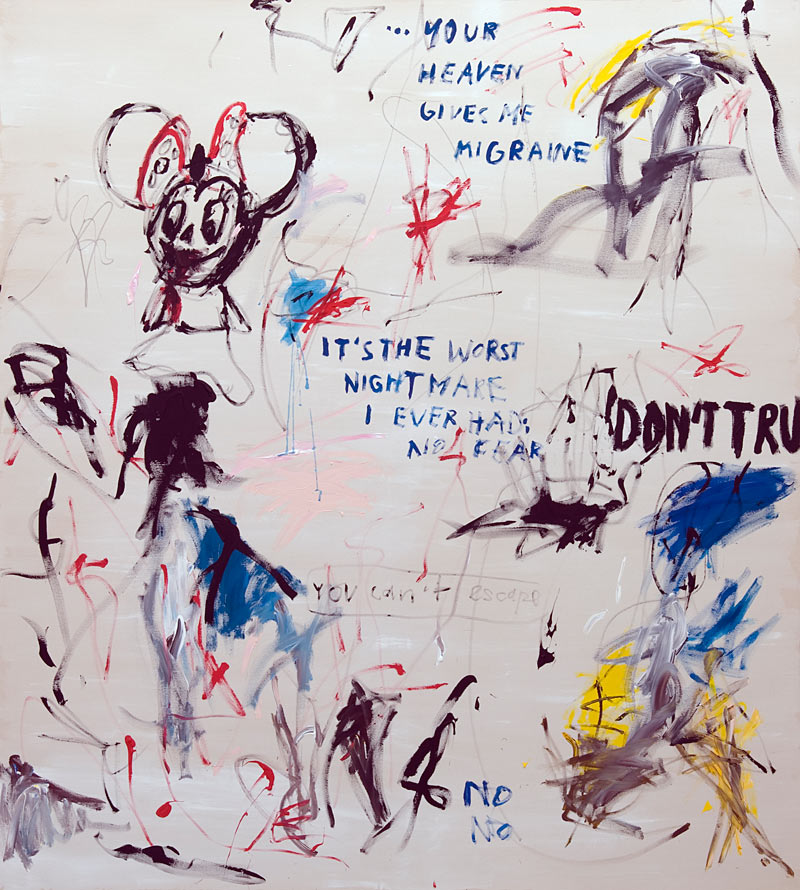

Alongside her video and neon works, Ditz’s paintings play a crucial role in this act of deconstruction—especially in how they engage with the iconography of male-domi- nated art history while infusing it with vulnerability, emotional turbulence, and personal narratives. The history of painting, like art history as a whole, has been largely defined by gestures, compositions, and themes shaped by male artists. Within this structure, the grand artistic gesture—the bold stroke, the aggressive composition, the monu- mental form—has often been associated with masculine artistic authority, from Abstract Expressionism to Minimalism, from Warhol’s Pop to Basquiat’s expressive chaos.

Ditz does not reject these histories but instead reclaims their language, using their forms to insert a different perspective—one that is gendered, unstable, deeply personal, and emotionally raw. While these artistic references carry the weight of tradi- tion and canonization, Ditz fills them with disruptive, subversive content—whether it is song lyrics, personal reflections, or fragmented, vulnerable expressions of female experience.

Music, particularly lyrical fragments from pop songs, becomes a critical layer within her paintings, further complicating their art historical references. Lines from artists like Amy Winehouse, Le Tigre, and Britney Spears appear not as detached pop-cultural citations but as deeply felt emotional statements—statements that blur the boundaries between personal pain, public image, and collective memory. A lyric like "Back to Black" (Amy Winehouse) carries an intense emotional weight, not just because of its melancholic content but also because of the cultural narrative surrounding Winehouse herself—a woman whose talent, struggles, and ultimate downfall became fodder for media spectacle. By incorporating such fragments, Ditz’s paintings refuse the detachment of traditional art historical references, replacing them with an intimacy that is both vulnerable and confrontational.

There is an inherent tension in these works: the grand tradition of male artistic gestures is confronted with a perspective that is often dismissed or trivialized within that same tradition—emotion, vulnerability, pop culture, and female experience. Rather than positioning herself outside these artistic legacies, Ditz engages with them from within—using their language, but on her own terms.

This destabilization of artistic hierarchy and authority mirrors the other elements of I’M JUST A CONCEPT, particularly the videos, neon works, and sculptural interventions, which all highlight the rigid structures that shape identity, emotion, and representation. Ditz does not simply critique these systems—she infiltrates them, reworks them, and reveals their fractures.

Through the interplay of video, neon, painting, and sculpture, I’M JUST A CONCEPT constructs a fragmented yet cohesive investi- gation into how media, particularly horror cinema and pop culture, dictate how emotions are performed and how identities are shaped. Ditz’s use of looping and repetition not only critiques the manipulation of women’s suffering in film but also engages with the broader question of authenticity in an image-saturated world. The exhibition’s layered visual language—drawing from horror, conceptual art, Minimalism, and pop music—creates an environment where familiar symbols begin to collapse into one another, revealing their under- lying artificiality.

By deliberately distorting and subverting these recognizable forms—whether a neon sign, a sobbing woman, a cinematic trope, or a canonical artistic gesture—Ditz forces the viewer to confront the illusion of emotional authenticity, the constraints of identity, and the pervasive influence of media in shaping what we believe to be real. Through repetition, appropriation, and disruption, I’M JUST A CONCEPT challenges the historical and contemporary systems that define whose voices, emotions, and experiences are granted space and authority within visual culture.

This method of appropriation, repetition, and subversion is not confined to I’m Just a Concept but extends across Ditz’s broader body of work. Even within her abstract paintings, similar strategies emerge—gestures and compositions that recall iconic, male-domi- nated art-historical forms but are infused with a distinctly different perspective, one that introduces instability, emotion, and a gendered lens. Titles, too, become a site of intervention, often referencing female experience, pop culture, or cinematic tropes, further blurring the boundaries between the personal, the cultural, and the historical while resisting the exclusionary traditions of art history. In doing so, Ditz not only engages with art history but actively reclaims and reconfigures its language, inserting narratives, emotions, and perspec- tives that have long been overlooked or dismissed.