Lola Mense on the exhibition

How to Disappear

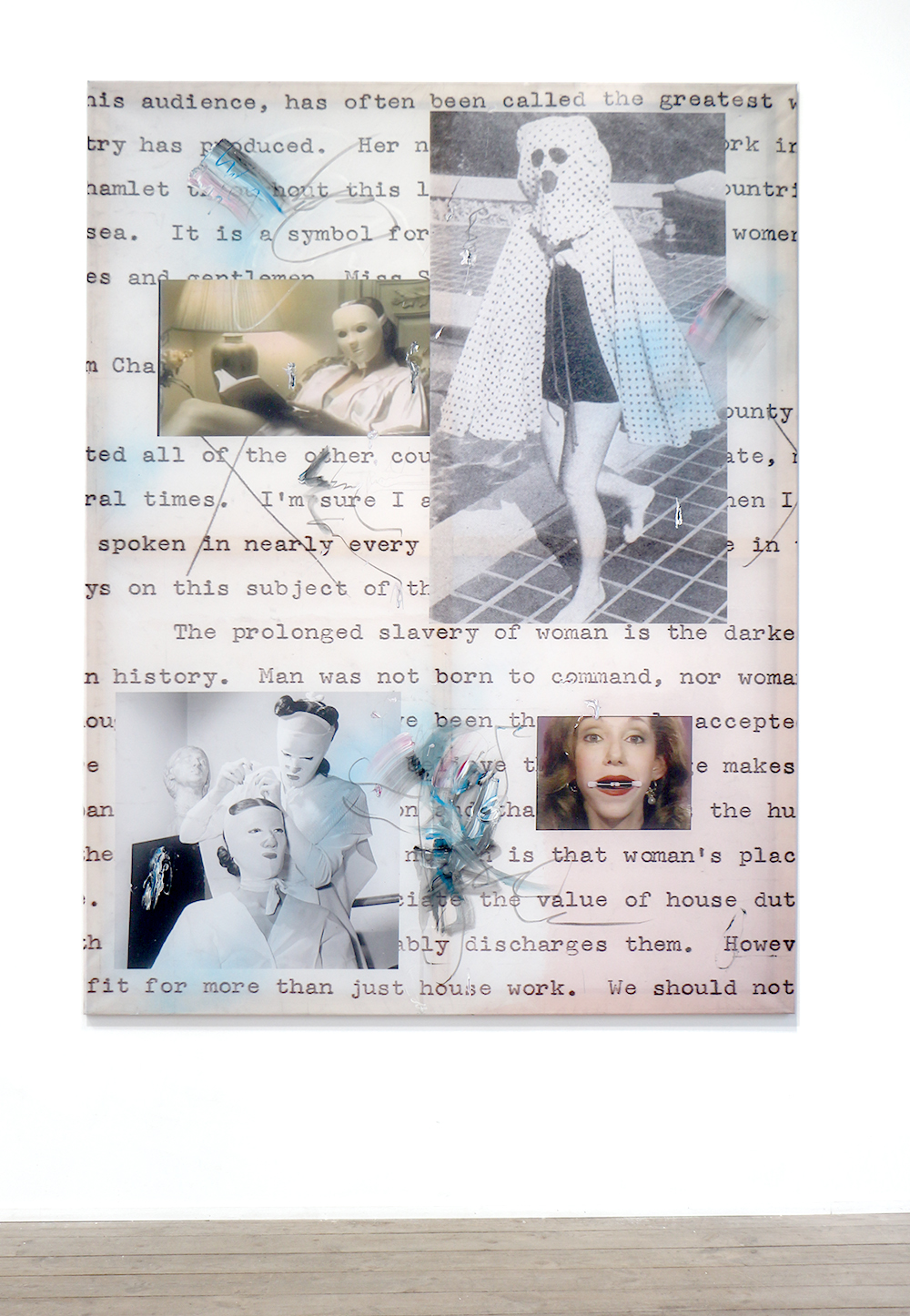

Two details in the artist Cordula Ditz’s highly condensed printed wall pieces gesture back toward sixteenth-century Great Britain, where a metal device was invented that, for three centuries, would serve to strip women and, later, slaves of their freedom, self-determination, and integrity. The ‘scold’s bridle,’ a kind of iron muzzle made of several braces and a mouthpiece, was used to punish, humiliate, and simply silence ‘problematic’ women. In Ditz’s works, aspects of oppression, impuissance, and loss of control in various forms associated with the stereotype of the helpless woman appear side by side with historic examples of resistance. Depictions of ghostly apparitions point to Spiritualism as practiced in nineteenth-century America, where being cast in the role of the medium capable of communication with spirits helped women raise their voices and publicly address issues of contemporary social and political relevance for the first time. The two hatchets resting on the gallery’s floor like props, lending the exhibition space a stage-like aura, are made of glass; their fragility contrasts with their versatile symbolism of force—they, too, may be taken as emblems of the American women’s movement. Signifying violence, they recur in one illustration in the large-format pictures. It shows a woman attacking a painting with a hatchet: the suffragette Mary Richardson, who had served six months in prison, is laying into Velázquez’s Venus at the National Gallery on March 10, 1914. She will later justify the act as a protest against the arrest of her fellow campaigner Emmeline Pankhurst.

Crossing media boundaries, Ditz’s practice investigates the ways in which cultural history conditions perspectives on who is entitled to what and patterns perceptions as well as the strategies of self-empowerment the defeated resort to. At first glance, this strategy would seem to collide with the abstract-expressionist style of the four canvases. Combining fierce sweeping gestures with graphical elements and restrained expressiveness, they counteract the material’s subversive determinacy with an airy—though deceptive—lightness. These works are titled Post Automatic Painting and numbered—a contradiction in terms: standardization versus chance. The initial impression of fluent ease gradually resolves into a lived reality increasingly shaped by mechanisms of control that also figures in Ditz’s video pieces. Fainting presents a series of women having fainting fits, accompanied by music from hypnosis videos on YouTube supposedly featuring special frequencies that can dispel inner conflicts and the error known as overthinking. The looped video consists of footage samples dating from between the dawn of the moving image and today’s digital media imagery.

Film comes to play a special role in Ditz’s approach to (pop)cultural history. Alison Landsberg has coined the concept of “prosthetic memory” to describe the way film, as an icon of mass culture, begins to act as a joint between individual and collective consciousness. The dissemination of others’ experiences through film expands consciousness—formerly the yardstick of individuality—into a postmodern storehouse of knowledge, primarily through technical interventions of affect transfer. As early as the eighteenth century, art critics argued that the beholder before a painting needed to forget his or her own standpoint in order to assimilate the affects immanent to the work in a performance of identification with the depiction and its intended meaning. Like the cinema with its darkened auditorium, the plethora of shocking information substantiated by visual material that circulates on the internet presents as a logical extension of that virtual fusion with a collective worldview. Blessing or curse?

Ideally, collective memory as analyzed by Maurice Halbwachs strengthens not only our sense of community but also a democracy animated by empathy, one in which the lives—and, more particularly, ‘the pain’—‘of others’ (Susan Sontag) are on our personal agendas. Can artificial or artistic impulses transmitted by this experiential prosthesis help us overcome ostensible dichotomies between self and other, between genders, between ethnic groups? Meanwhile, any collectivity contains the danger of abuses of power: when ‘truths’ spread by the media and reinforced by their affective impetus become tools of propaganda so that we lose control of our own identities and, more importantly, our moral compass. Whether through critical meta-media engagement or now more, now less authentic physical performances of impuissance and sudden faintness, any loss of control is felt as an instant of personal integrity forfeited. At the other end of the spectrum, the abstract painter must deliberately cast off the burden of civilization that is composure, breaking all social strictures so that his or her genius can achieve unadulterated self-expression. A disconcerting nexus emerges between bourgeois ideas of creative freedom, the deep cuts hewn into the back of a lacerated Venus, the cool and flawless surface of the glass hatchet, and the exhausted media worker who is constantly on air.

HOW TO DISAPPEAR

Cordula Ditz’s HOW TO DISAPPEAR examines the enduring tension between visibility, oppression, and empowerment, weaving together centuries of cultural history with a sharp focus on the mechanisms of control and resistance. Through an intricate combi- nation of historical references, contemporary media, and abstract expression, the exhibition interrogates how systems of power silence individuals and how acts of defiance can carve pathways to agency.

At the core of the exhibition is the theme of silencing, embodied by the recurring reference to the sixteenth-century British “scold’s bridle.” First documented in 1567 and last recorded in use in 1856, this cruel metal device was designed to muzzle and publicly humiliate women deemed “problematic” or accused of gossiping. While its physical function was to silence, its symbolic power extended far beyond the immediate act, reinforcing societal narratives of control and submission. The scold’s bridle exem- plifies how the history of silencing women has itself been erased from historical narratives, rarely appearing in history books despite its role in suppressing female voices for centuries. By bringing this unsettling artifact into her work, Ditz forces viewers to confront the historical mechanisms of silencing and to reflect on how similar forces persist in contemporary forms, albeit more covertly. This historical erasure extends into the history of the women’s movement itself. Often reduced in popular imagination to images of elderly women holding banners, the suffrage movement was, in reality, a dynamic and multifaceted campaign that employed diverse tactics, including civil disobedience and direct action. Through references like the scold’s bridle and suffragette Mary Richardson’s bold attack on Velázquez’s The Rokeby Venus, HOW TO DISAPPEAR reclaims these erased narratives, situating women’s resistance as a powerful counterpoint to the systems of silencing that sought to control them.

The theme of rebellion is particularly evident in Ditz’s sculptural centerpiece: two handmade glass hatchets placed on the gallery floor. Crafted to match the size and form of real hatchets, the sculptures convey a sense of both fragility and latent violence. One hatchet, made entirely of transparent glass, reflects light with pristine delicacy, its fragility a stark contrast to its association with destruction. The second hatchet, equally fragile, features red, flowing details within the glass, evoking the appearance of paint dissolving in water. This subtle coloration suggests violence and disruption without explicitly depicting it, leaving viewers to grapple with its symbolic weight. These objects transform an instrument of violence into a contemplative work of art, embodying the tension between empowerment and vulnerability. The hatchets’ symbolism extends into one of Ditz’s large-scale prints, which references Mary Richardson’s 1914 attack on The Rokeby Venus. Richardson’s protest against the arrest of suffragette leader Emme- line Pankhurst transforms the hatchet into a historical symbol of defiance and self-assertion, linking past struggles to contemporary discourses on agency and resistance.

The exhibition’s paintings further expand its conceptual depth, divided into two distinct series that occupy contrasting aesthetic and conceptual realms. The first series, created on printed flag fabric, combines dense collages of appropriated imagery with traces of abstract painting techniques. Using acrylic, spray paint, pencil, and oilstick, these works intertwine historical memory with contemporary critique, layering mediums to construct complex visual narratives. In these collages, traces of sweeping abstract gestures sit alongside meticulously arranged fragments of cultural and historical images, inviting viewers to decode the interplay between chaos and control. The second series, Post Automatic Painting, draws its name from the spiritualist practice of auto- matic writing and drawing—a technique later adopted and celebrated by the surrealists. These abstract canvases, also created with diluted acrylics, oilstick, and expressive brushstrokes, reflect on the paradox of freedom and control. The deliberate yet fluid gestures evoke the balance between spontaneity and constraint, mirroring societal mechanisms of standardization and individu- ality. By referencing spiritualist practices, the works also connect to the historical intersections of the mystical and the political, where suppressed voices found ways to speak through unconventional means.

In the center of the exhibition space, two large flatscreens mounted on poles spanning from floor to ceiling introduced a dynamic, immersive element to the installation. These video works, placed at eye level in the middle of the room, confronted viewers with moving imagery and sound that deepened the exhibition’s themes. The first video, FAINTING, presents a looped

montage of fainting women, spanning early cinematic depictions to digital media imagery. The title draws on the German word for fainting, Ohnmacht, which translates to "without power." This linguistic connection underscores the cultural associations of fainting with loss of agency. In the Victorian era, fainting was not only normalized but idealized; a frail and delicate appearance was considered the height of feminine beauty, and fainting itself became a symbol of desirable fragility.

The video’s soundtrack incorporates frequencies purported to stop "overthinking," a critique of the self-help videos that often target women. These pseudo-esoteric videos perpetuate the idea that women’s natural thought processes are flawed—“too much,” too emotional, or too scattered. Women, especially young women, are frequently told to stop overthinking, a phrase that trivial- izes their concerns and dismisses their intellectual autonomy. By implying that their mental energy is misdirected, such rhetoric invalidates women’s thoughts and obstructs their ability to explore curiosity or pursue independent ideas. The soundtrack’s hypnotic cadence becomes both a reflection of this societal conditioning and a subversive tool to expose it. Within this context, the act of fainting is reframed—not merely as a symbol of fragility but as a refusal to comply with societal expectations, a moment where the body takes control by relinquishing it.

The second video, I'M ON YOUR SIDE, juxtaposes fragmented found footage with a disquieting voiceover. The video begins with an image-in-image composition: a fleeing woman overlays a stony coastline, where waves crash relentlessly against the shore. This striking visual metaphor is accompanied by a soothing yet commanding female voice that grows increasingly ominous:

“Deeper into my control. It just feels so good to obey. It feels so good to give in. It feels so good to be deeply programmed. My words are programming your mind. Yes, my words are feeling my words taking over. Feeling my words now controlling you. My words controlling every inch of you, every cell. Feeling my words running through you like electricity. Feeling controlled like a robot. A mindless, obedient robot.”

As the video progresses, the imagery shifts to a woman stabbing a portrait, repeatedly driving the knife into the face of the painting. This act of destruction is both visceral and symbolic, evoking themes of erasure, rebellion, and the defiance of imposed identities. In its final moments, the video focuses on a teenage girl lying on her bed, speaking to an unseen person. She says, “It’s so scary to think that you can just vanish and no one will ever know.” This haunting statement underscores the exhibition’s explo- ration of disappearance—not just as an act of oppression but also as a profound existential fear.

The immersive audio work, HOW TO DISAPPEAR, plays continuously throughout the gallery, creating an enveloping sonic landscape. This spoken hypnosis guides listeners through a meditation on vanishing, framing disappearance as both an instrument of control and a potential act of agency. The soothing yet unsettling tone mirrors the exhibition’s overarching themes, encouraging visitors to consider the psychological dimensions of invisibility, both as a means of escape and a form of resistance.

A haunting and destabilizing atmosphere pervades the exhibition through the presence of neon tubes scattered across the gallery floor, with one standing upright in a corner. Programmed to simulate the flicker of broken lights, the neon pieces evoke a sense of instability and fragility. These subtle yet potent interventions reinforce the exhibition’s exploration of disarray, loss of control, and the tenuous nature of empowerment within oppressive systems.

Through its carefully curated elements, HOW TO DISAPPEAR draws from diverse mediums and historical references to construct a deeply resonant exploration of silencing, memory, and empowerment. By juxtaposing historical symbols like the scold’s bridle with narratives of resistance, such as Mary Richardson’s bold defiance, Ditz constructs a dialogue that spans centuries while remaining acutely relevant to contemporary concerns. The interplay of fragility and power, visibility and erasure, invites viewers to consider how acts of disappearance—both forced and chosen—shape our understanding of agency and control.

In HOW TO DISAPPEAR, oppression is never the endpoint. Instead, the exhibition reveals the subtle, often invisible ways resis- tance can emerge, whether through the fainting body, the fractured voice of the spiritualist medium, or the symbolic violence of a glass hatchet. Ditz challenges us to reconsider the narratives we inherit and the systems we perpetuate, opening a space for reflection on how histories of disappearance and resistance continue to shape the present.