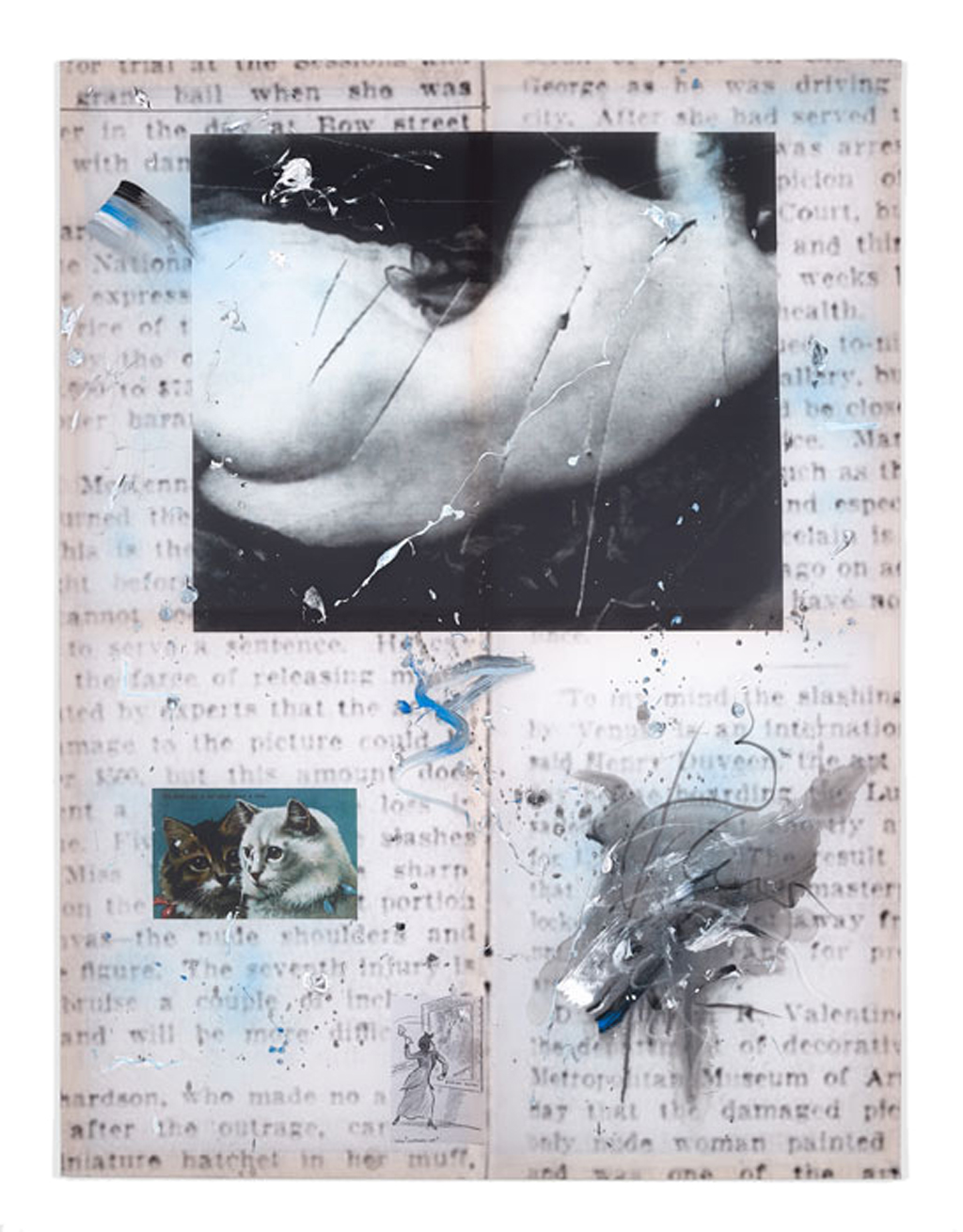

Two glass hatchets rest on the gallery’s dark wood floor like props. Exuding a faint sense of menace, they lend the exhibition space a stage-like quality. Ontologically speaking, the aesthetic objects made of glass are hybrids: their material bodies are fragile, while their form signals brute force. A versatile symbol adopted by the American women’s movement and others, the hatchet looks back on an extensive cultural history. In Cordula Ditz’s exhibition, it signifies violence first and foremost. The motif recurs in a small illustration on one of the large-format pictures on view. It shows a woman—to judge from her attire, she is an early-twentieth-century daughter of the bourgeoisie—laying into a painting with a hatchet. She is Mary Richardson, a suffragette who has served six months in prison and will later justify her assault on Velázquez’s Venus at the National Gallery on March 10, 1914, as a protest against the arrest of her fellow activist Emmeline Pankhurst.

In a work that crosses media boundaries, Cordula Ditz scrutinizes the perspectives informing the demands and perceptions of history’s underdogs, their strategies of empowerment and the cultural contexts that shaped them. ‘When spiritualism rose to popularity in the United States around the mid-nineteenth century, communication with the other world was described, in keeping with the era’s preference for scientific metaphors, as a kind of telegraphy that required two antithetical poles. The minus pole carried feminine connotations, and so women served as mediums: they alone were thought to be capable of entering into contact with the spirits. Women had hitherto been largely prohibited from appearing before public audiences and giving speeches, but now an opportunity opened up for them to do just that (…) Authorized by the conjured spirits of dead men, they were able to achieve economic success, paint, write, and expound publicly on issues of social and political relevance. In this way, spiritualism not only facilitated distinguished careers such as that of Victoria Claflin Woodhull Martin, the first woman to run for President of the United States and the first to head a brokerage firm on Wall Street; it also paved the way for the women’s movement.’*

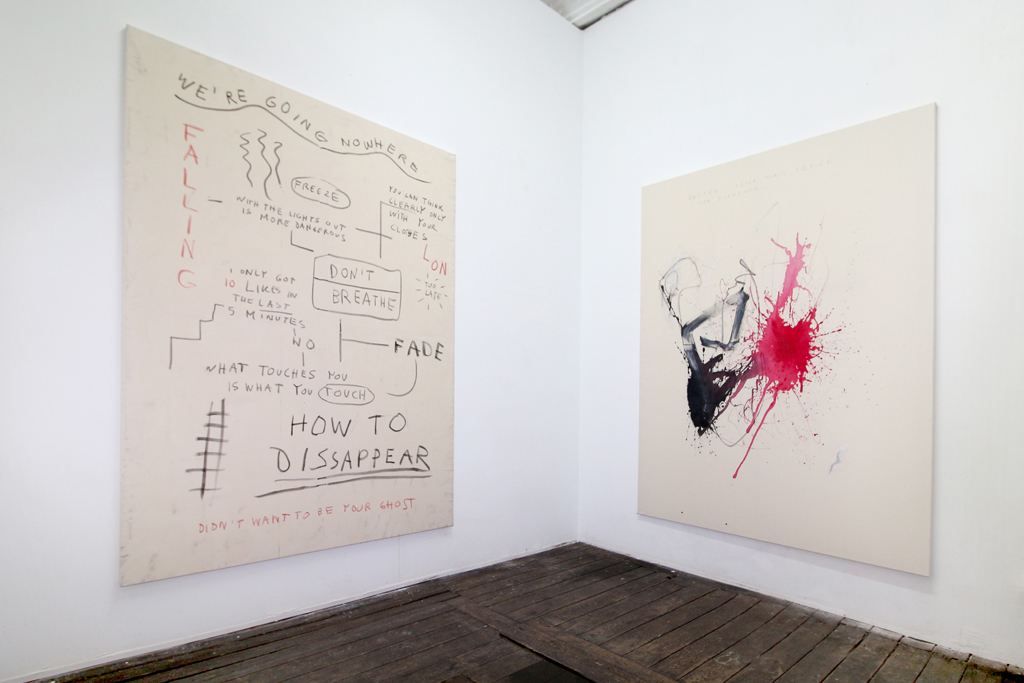

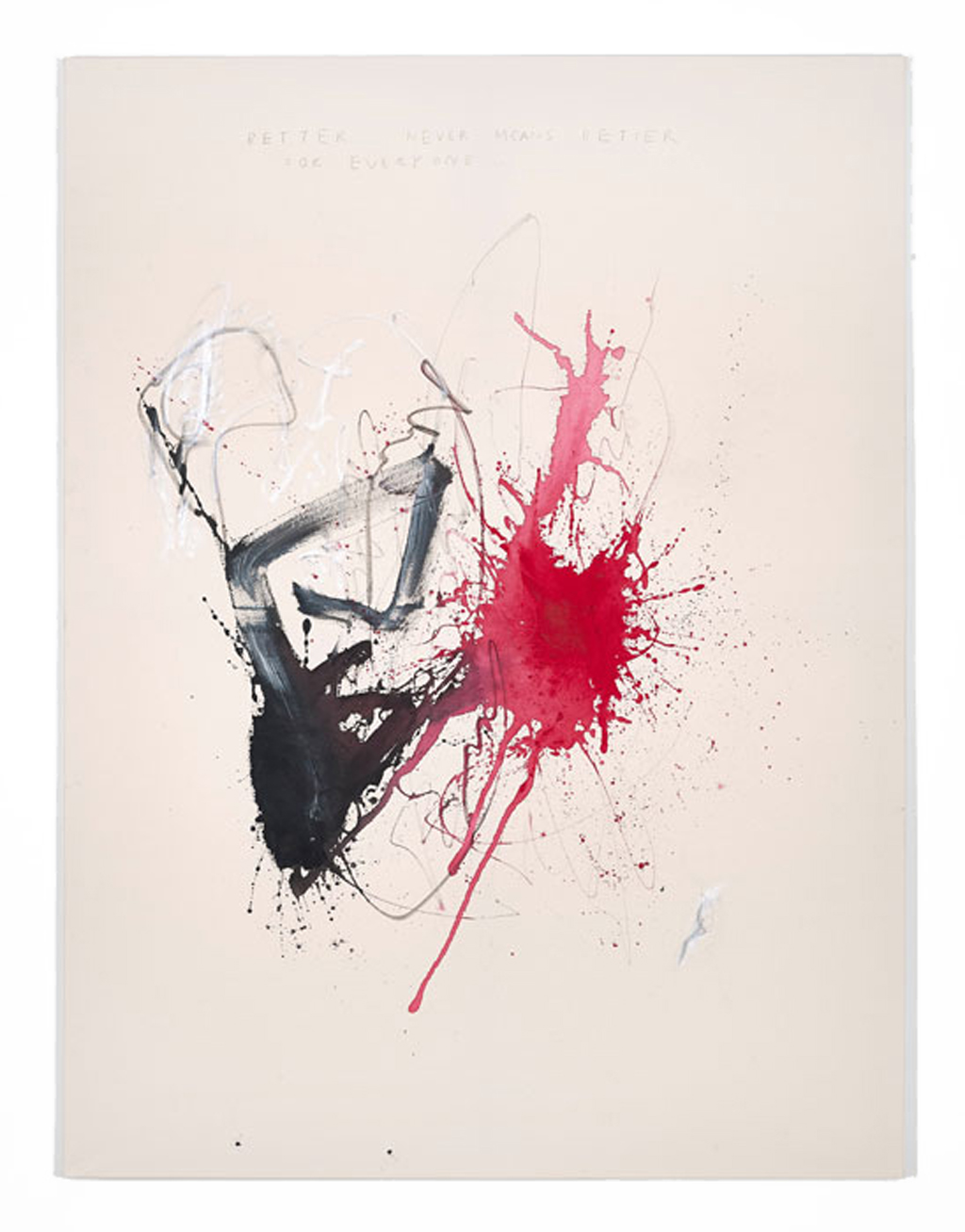

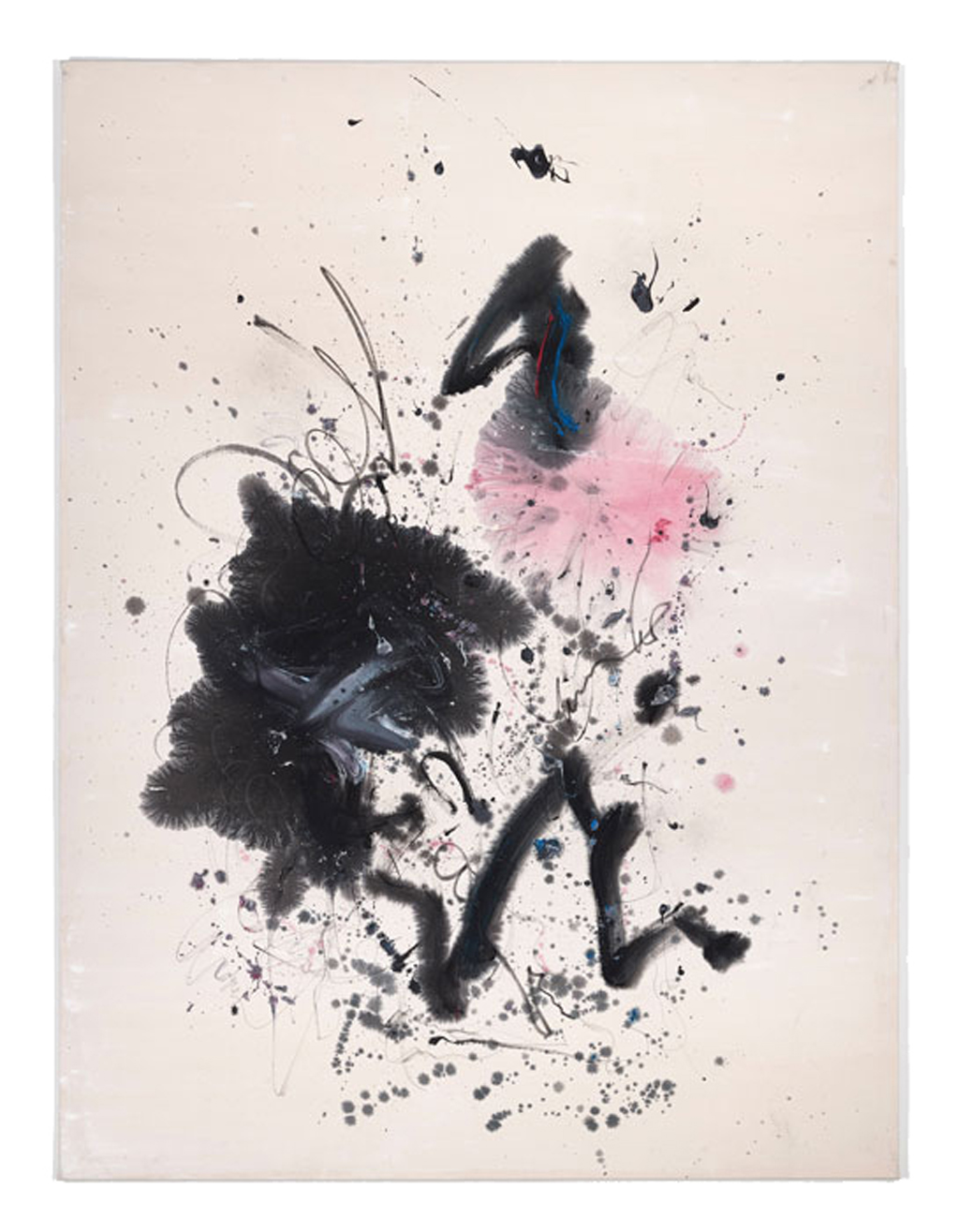

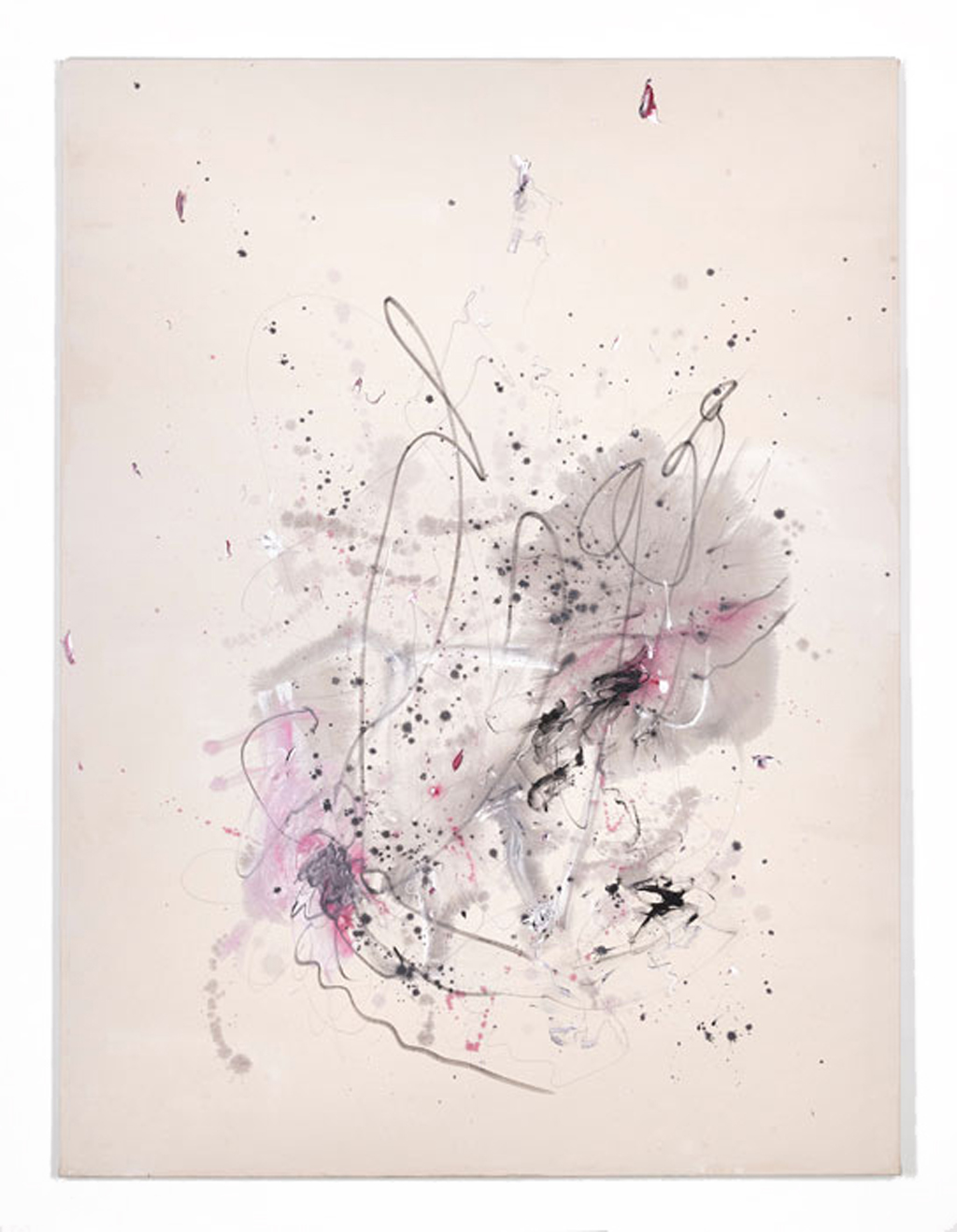

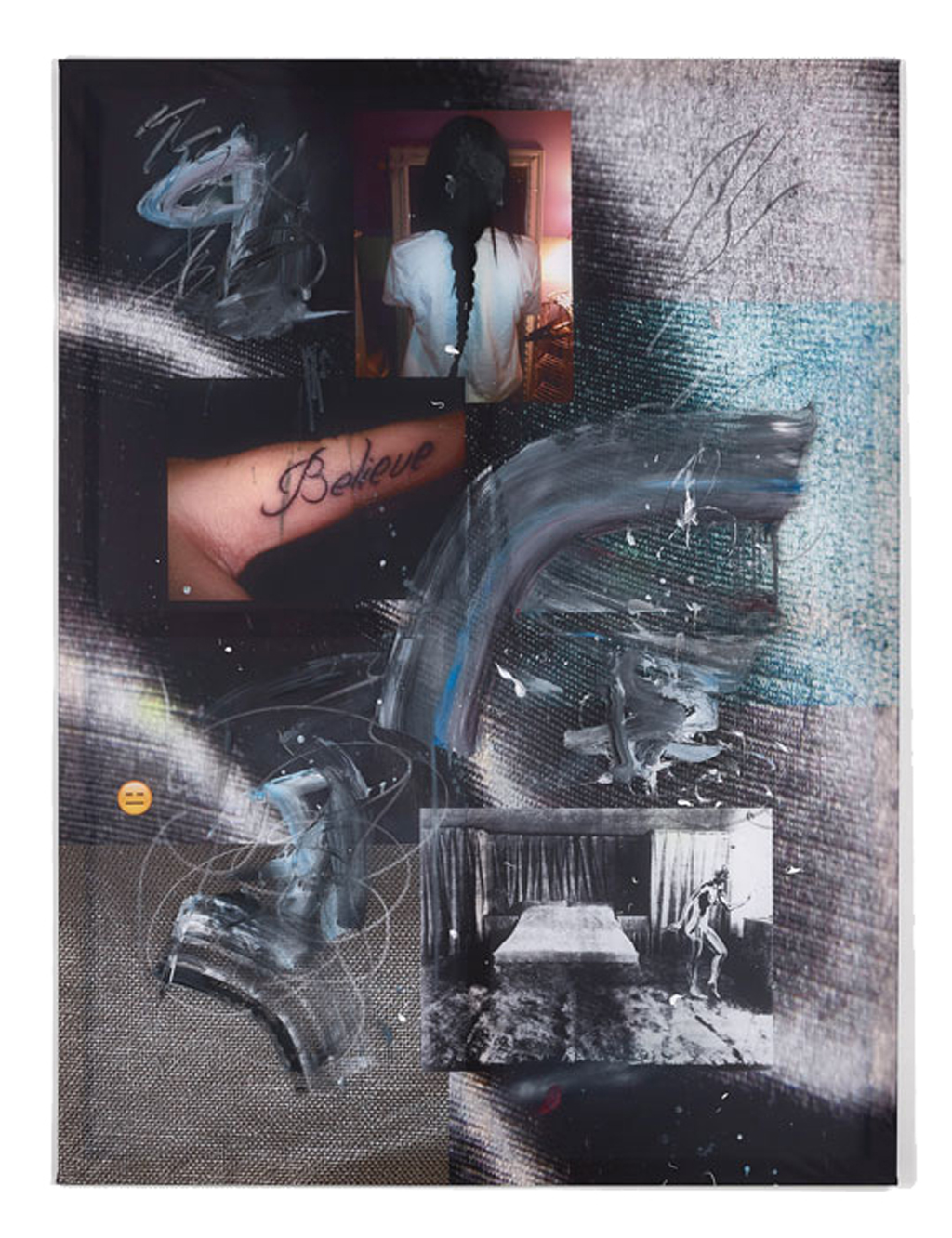

In contrast with the prints featuring highly condensed appropriated imagery from a variety of sources, the abstract gestural canvases feel positively airy. Diluted acrylic paint in cool hues, applied in a combination of ferocious brushwork, graphical elements, and subdued expression, spread over barely primed surfaces. These pictures bear the title Post Automatic Painting and are numbered consecutively—a contradiction: standardization versus randomness. Post, in this context, points to the paradoxical transformation of everyday life in a society increasingly remolded by mechanisms of control, subjectivity, and post-factual politics. The video Fainting arrays different examples of women’s fainting spells, accompanied by music from YouTube hypnosis videos that promise to resolve inner conflicts and what is called overthinking through exposure to special frequencies. Ditz, who has more than once examined aspects of oppression, disempowerment, and the loss of control through the lens of the peculiar role model of the defenseless woman in cultural history and pop culture, collected footage ranging from the early days of the silver screen to contemporary digital media imagery and compiled it in a loop. From the awkwardly acted slow-motion collapse to the authentic dizzy spell—the pictures illustrate the loss of control as an instant in which personal integrity is forfeited. Composure is the burden of civilization. The abstract painter, however, must deliberately overcome it, casting off all social strictures so that his genius can achieve unadulterated self-expression. A disconcerting nexus emerges between bourgeois ideas of creative freedom, the deep cuts hewn into the back of a lacerated Venus, the cool and flawless surface of the glass hatchet, and the exhaustion of the media worker who is constantly on air.