Photos by Fred Dott / 2022 Kunsthalle Hamburg

Photos by Volker Renner / MIND the GAP, Bieberhaus Hamburg

YOU MAY NOT KNOW HIM, BUT

Cordula Ditz’s installation YOU MAY NOT KNOW HIM, BUT is a layered exploration of history, memory, and the narratives that shape our understanding of the past. Created for an exhibition in the historic Bieberhaus near Hamburg’s main train station as part of the MIND the GAP program, curated by Sven Christian Schuch, the work transforms the building’s disused paternoster elevator into a symbolic and reflective space.

At the heart of the installation is the story of Helmuth Hübener, a 17-year-old resistance fighter whose life intersected with the Bieberhaus in 1942. While training in social administration in the building, Hübener listened to forbidden BBC broadcasts and distributed anti-Nazi leaflets with his friends Rudolf Wobbe and Karl-Heinz Schnibbe. Arrested and executed by the Nazi regime, Hübener’s courage remains largely unacknowledged in Germany, overshadowed by figures like the Weiße Rose. Yet in the United States—particularly within the Mormon community to which he belonged—Hübener’s legacy is actively preserved, reflecting the generational and cultural differences in how memory is constructed and maintained.

A key component of the installation is a video work that juxtaposes materials about Hübener exclusively from U.S. sources with scenes from German National Socialist propaganda films. The U.S. material spans diverse formats, from book advertisements and documentaries to reenactments by a Mormon theater group and personal reflections by teenagers. One teenager begins his video with the line “You may not know him, but ...”—a sentence that inspired the installation’s title. The boy places Hübener alongside Anne Frank as a personal hero, framing him as an essential yet underappreciated figure in resistance history.

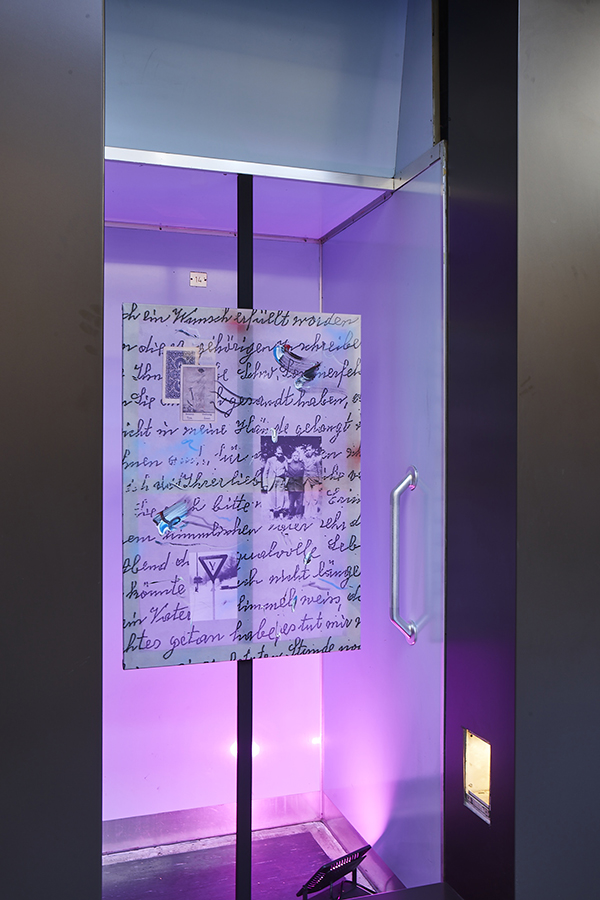

The physical installation in the paternoster further extends this dialogue. The cabins carry real palm trees, evoking the memory of the grand café that once occupied the Bieberhaus’s ground floor. On the top floor, an inverted palm tree references an urban legend about the dangers of riding a paternoster past its uppermost level—a myth tied to a nonexistent Charlie Chaplin film. While this fabricated story has endured in cultural memory, Hübener’s heroic resistance remains relatively forgotten, prompting reflec- tion on why some narratives persist while others fade.

Within the paternoster cabins, Ditz includes paintings that further engage with themes of observation and historical memory. Some feature scenes of people on sightseeing buses from the 1940s, passing the Bieberhaus, where a popular photo spot once existed. These figures are always looking in the opposite direction, their attention fixed elsewhere. In the context of the installa- tion, they now gaze at the viewers who, in turn, are looking at the paintings, creating a layered interplay of witnessing and being witnessed. This subtle reversal highlights how acts of observation shape and redefine historical narratives, inviting visitors to consider their own role in the act of remembering.

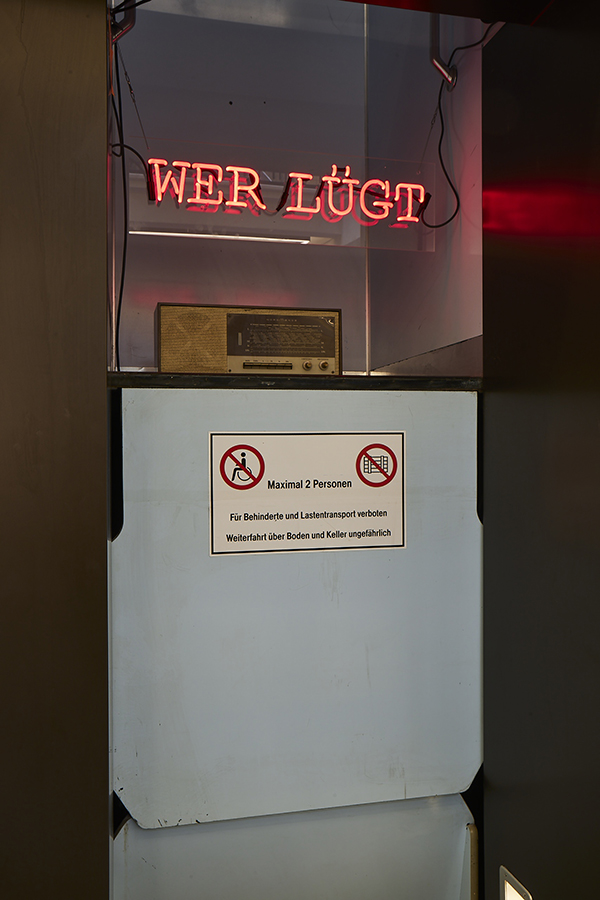

One painting also depicts Charlie Chaplin upside down, layered over a digitally collaged flyer made by Hübener. This interplay of myth and memory further emphasizes the ways in which stories are constructed and prioritized, inviting viewers to question the forces that shape collective memory. A neon phrase, “Wer lügt” (“Who is lying?”), taken from one of Hübener’s leaflets, punctuates the installation, linking his fight against propaganda and misinformation to contemporary concerns about media and truth.

The broader atmosphere of the installation is equally compelling. Radios scattered throughout the space recall Hübener’s subversive listening to BBC broadcasts and the Nazi regime’s weaponization of radio. Pink lighting, with its historical evolution from a “masculine” to a “feminine” color, reflects broader cultural shifts, while a mirror with flickering lights symbolizes a passage for forgotten spirits, blending themes of reflection and alternate realities with the installation’s meditation on memory and loss.

Ditz also draws attention to the Bieberhaus’s layered history, recalling the art salon of Maria Kunde, once located in the building. Among its exhibitions were works like the Friedrichsberg Heads by Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, an artist later murdered under the Nazi “euthanasia” program. This connection underscores the Bieberhaus’s role in facilitating institutionalized atrocities, weaving the building’s layered past into the installation’s broader exploration of resistance and complicity.

Adding an element of speculation, Ditz invited local fortuneteller Esmeralda Rosenberg to predict the future of the Bieberhaus during the exhibition’s opening. This act blends historical reflection with imaginative storytelling, offering a contemplative space where past, present, and future converge.

Through its intricate layering of video, objects, and site-specific references, YOU MAY NOT KNOW HIM BUT becomes a meditation on the fragility of memory and the construction of historical narratives. The installation invites viewers to confront the discomfort of witnessing: to reflect on whose voices are amplified, whose are lost, and how memory shifts across generations. In a world where fabricated stories endure while real acts of courage fade, the work poses a critical question: What does the way we remember—or forget—say about us?