Photos by Fred Dottt / Kunstverein in Hamburg 2020

Photos by Helge Mundt / Galerie im Marstall Ahrensburg

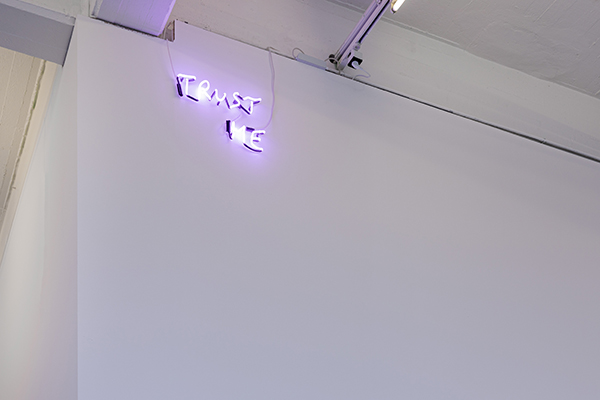

SILENT ALL THESE YEARS Tobias Peper

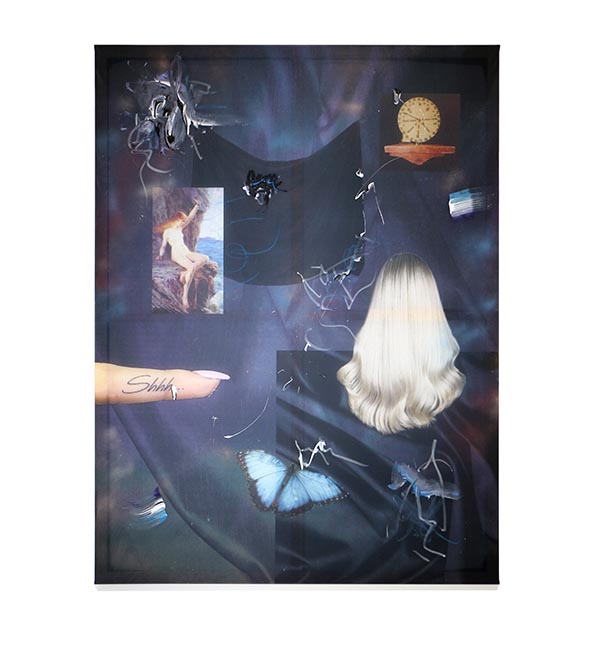

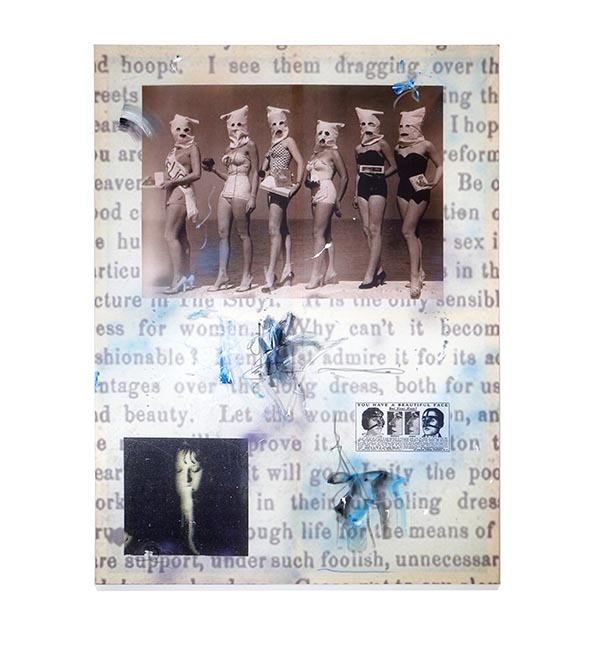

Cordula Ditz’s work scrutinizes the ways in which our ideas about gender roles and identity are constructed, reiterated, and solidified—the media play a salient role in this process—and how they inform our conscious as well as unconscious minds. To this purpose, she gathers materials she finds online and in books, magazines, and films and integrates them into paintings and videos in the form of collages or montages. The result is a rich imagery that is open about its genesis and performative nature in order to prompt reflection on media representation and the production of normative codifications.

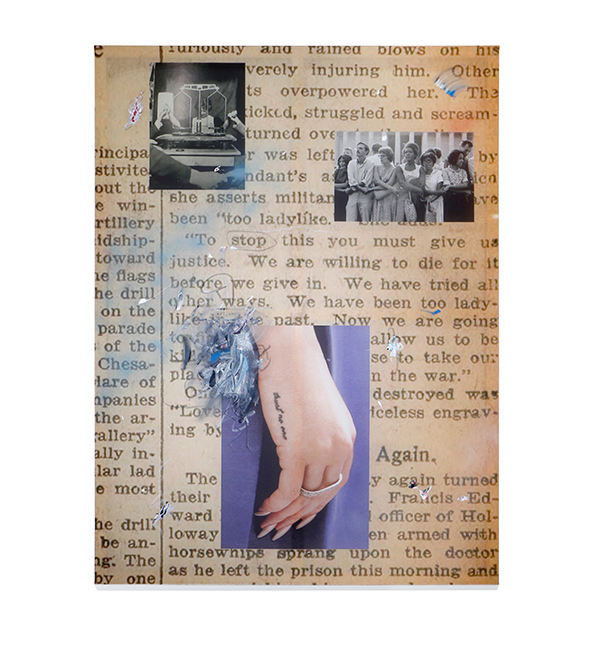

Running for just under half an hour, the video Your Silence Is Very Disturbing (2019) revolves around women’s expe- rience of intersectional and enduring discrimination and how it affects the social conception as well as self-image of what it means to be a woman or a man. Silence, as the title indicates, is a recurrent motif in the work. Ditz has edited a rapid succession of scenes that illustrate silence, the act of silencing, and the loss of one’s own voice as well as the self-empowerment that comes with breaking the silence. How powerful voices and their suppression can be is demonstrated by a prominent story that Ditz’s work explicitly refers to. On several occasions, she cuts to interviews related to the #MeToo movement, arguably one of the most widely reported phenomena of recent years and one whose impact has been considerable: often communicating through social media, an alliance of women raised accusations of sexual assault and rape, revealing how a sweeping code of silence, upheld mostly by men, has perpetuated the brutal structures that enable violence against women. The movement made international headlines because, in its early phase, many of the women who broke the silence were prominent actresses and the individuals against whom they brought charges were powerful Hollywood players. Rose McGowan, one of its protagonists, makes several appearances in Ditz’s video; she was among the first victims to accuse the omnipresent movie mogul Harvey Weinstein of sexual abuse, exposing what had been a well-kept secret for decades. To this day, people all over the world use the MeToo hashtag to give voice to their experiences of sexual harassment and rape. In addition to turning the spotlight on the perpetrators and the structures that emboldened them, they also hope to encourage others to break the painful silence, show solidarity, and build public awareness for the victims.

To sketch the larger nexus of causes and effects of which the #MeToo movement is but a part, Cordula Ditz complements the testimonials of the female victims with footage of prominent men like Matt Damon and others: appearing in talk shows and news reports, they offer oddly clumsy apologies for remaining silent for years or their social media comments on the ongoing debate; we sense their nascent awareness of their own responsibility as indirect enablers. To underscore the less than eloquent delivery of these pleas for absolution, Ditz intercuts the material with excerpts from a commercial for a Japanese apology agency that lets clients delegate the shameful act of expressing regret.

Ditz also includes clips from the political debate that illustrate the negative repercussions that breaking the silence can have. One of them is the so-called Pence Effect. Named after U.S. Vice President Mike Pence, who declared that he would not dine alone with a woman not his wife, the Pence Effect is a paranoid response to the #MeToo debate in which businessmen are urged to do everything to avoid being in a room with a woman without witnesses lest they become “victims” of baseless accusations of sexual harassment. On Wall Street, in particular— in an industry, that is to say, that was male-dominated to begin with—this effect has already demonstrably led to increasing segregation. In a grotesque twist, the struggle against discrimination and violence on one side fuels exclusion and unequal treatment on the other.

Beyond the #MeToo context, Ditz’s video repeatedly gestures toward the long and complex history of forms of oppres- sion, picking up, for example, on the discussion of the role of women in religious services as set out in 1 Corinthians, which enjoins them to silence in church. She also notes that society has still not fully reckoned with the history of slavery, and especially with the widespread rape of slaves by their “owners,” a historic example that is emblematic not only of the exploitation of an entire segment of the population but also of the brutality of (enforced) silence. Ditz brings these diverse narrative strands together with fast-paced cuts and by mixing and layering her footage, accompanied on the soundtrack by abrupt discontinuities and recurring musical themes. These devices extricate the individual stories from their historical settings and weave them into new contexts, deemphasizing the specific circumstances in favor of an overarching disquisition on the structural mechanisms of power that sustain discrimination, segregation, and the construction of gender roles and identities.

Your Silence Is Very Disturbing not only shows women as victims and accusers of violent men, it also draws attention to the subtler and less readily apparent effects of social standards of masculinity and femininity. Many scenes suggest the unremitting and indeed growing pressure that prevailing ideals of beauty exert, pushing people to strive for an unattainable perfection. The video includes footage about excessive fitness regimens, snippets from infant beauty pageants, and images of tightly laced corsets promising slimmer hips, as well as a recent trend: the beauty industry’s appropriation of meditation, originally a spiritual practice. So-called affirmations—a term from the New Age move- ment, describing positive messages addressed to oneself—are repeated ad nauseam like a mantra. In combination with the right breathing technique and concentration, they are supposed to strengthen the mind and even shape and modify the body. And so Ditz’s work features excerpts from meditation instructions that supposedly help the individual lose weight or even give him or her, in short order, a perfectly shaped nose. In reference to this curious inversion of a tradition that originally aimed to enlarge the consciousness and liberate the body, Ditz also created a series of printed yoga mats Why Refuse Happiness (2019). Instead of affirmations aiding in the pursuit of physical self-improvement, however, the mats are emblazoned with quotes from civil rights campaigners, feminists, and other activists—or, in one instance, with a simple “Shhhhh.” The objects are a hands-on invitation to reflect on the issues Ditz explores: we are prompted to meditate—literally—on statements such as “Your silence will not protect you” (the American writer and women’s and black civil rights activist Audre Lorde) or “Hope will never be silent” (the first openly gay American politi- cian, Harvey Milk). The quotes also appear prominently in Ditz’s video, where they are pronounced by heavily made-up

animated pairs of lips—again, the affirmation rite—and function as guideposts amid the torrent of materials. Commenting on what we have seen, they hint at how to make sense of it in a moment of reflection before the video takes off for its finale, in which a group of recognizably upset women prepare an underage bride for forced marriage. After this scene, Ditz’s work concludes with a sequence of automatically closing curtains that goes on for several minutes.

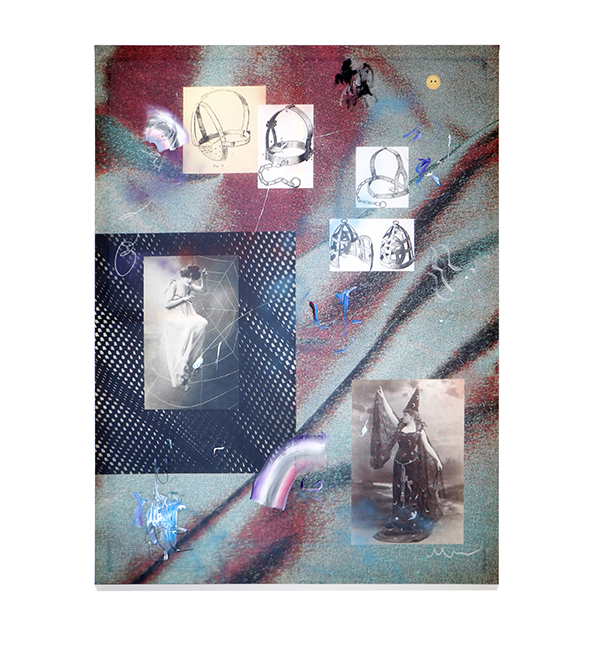

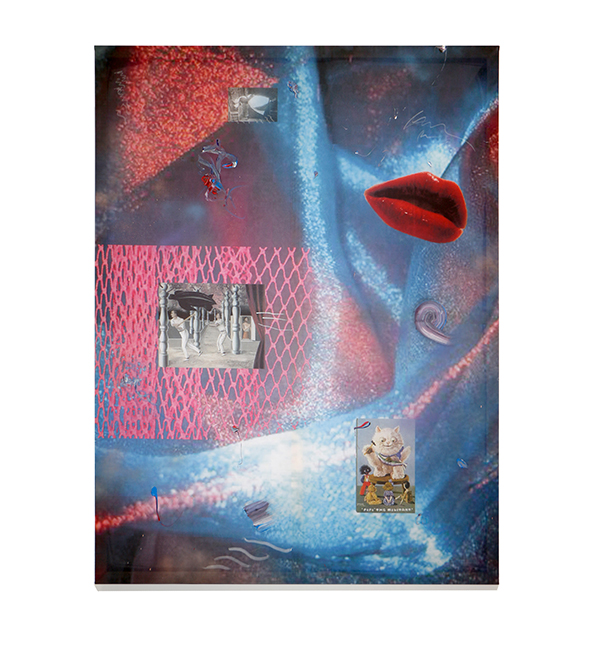

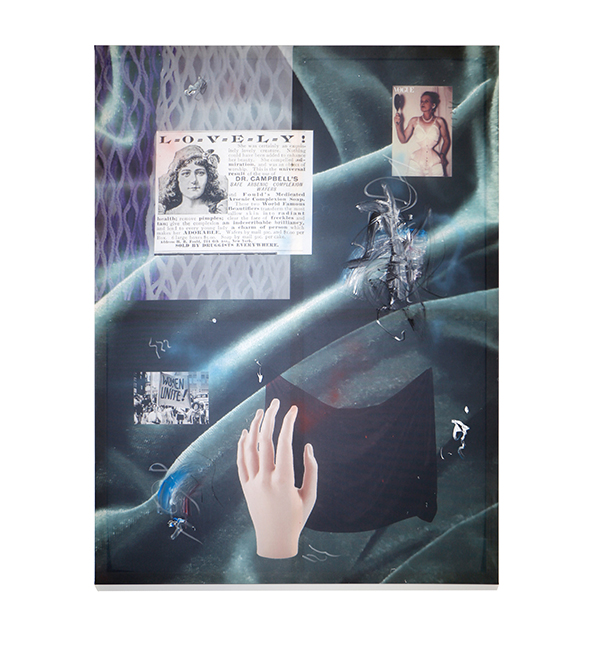

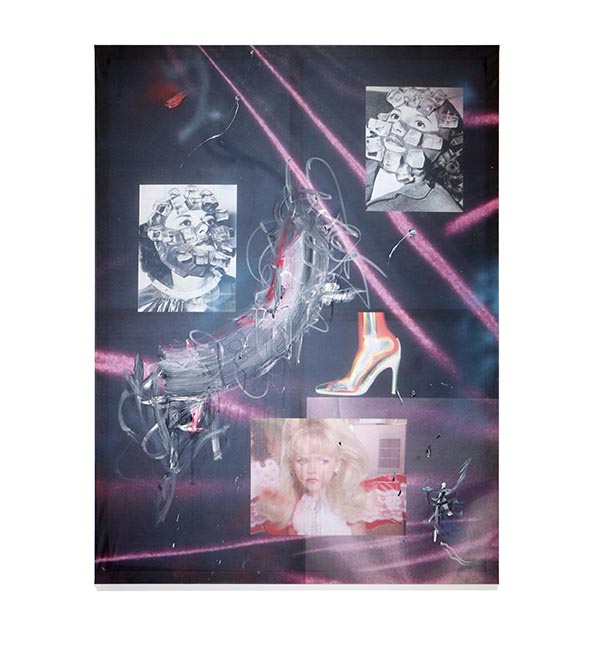

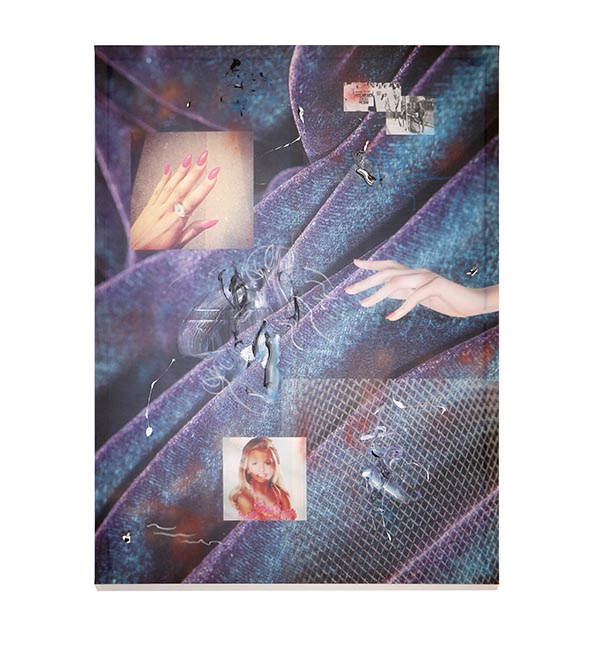

The motif of concealing and revealing with covering fabrics has a long tradition in painting. Ditz returns to it in many of the backgrounds in a series of paintings associated with the video. As digitally printed “linings” on translucent flag cloth, they are layered, in a static equivalent of video montage, with found images from books, magazines, and the internet. Pastose paint applied in gestural brush-work balances, consolidates, and accentuates the pictorial collages. These paintings, too, tell stories from the battles of the women’s movement, instances of oppression, and normative ideals of beauty—though now with a marked historical emphasis. We encounter the suffragette movement of the early twentieth century; selections from the 1895/1898 Women’s Bible; the Swedish painter Hilma af Klint, an early pioneer of purely abstract painting in Western art, whom the art-historical discourse has long neglected in favor of her male colleagues; historic face packs with ice cubes said to rejuvenate the skin; nose correction equipment; and even muz- zles that were used to silence women with brute force.

One of the paintings is titled It can do whatever we know how to order it to perform, after a quote from Ada Lovelace, whose photograph also appears in it. The British mathematician is best known for her work on the Analytical Engine, the mechanical computer designed by Charles Babbage. In the first half of the nineteenth century, Lovelace was the first to recognize that such a machine held much greater potential than merely performing calculations and published the earliest written algorithm that could have been carried out by the device. That is why she is regarded as the first programmer in the contemporary sense of the word, although some historians continue to downplay her achievement. The story links up with Ditz’s video, where she examines a recent similar episode. The American computer scientist Katie Bouman led the development of an algorithm for imaging a black hole and was a member of the Event Horizon Telescope team that published the first such image in the spring of 2019. A photograph was circulated in which she was visibly thrilled by this milestone achievement, and she attracted considerable media attention. Some commentators described her as the woman who had photographed the black hole, although Bouman never made such a claim or sought the limelight for her own contribution. She subsequently became the target of a smear campaign flanked, especially on social media, by hateful comments that belittled or even denied her accomplishments. While Bouman herself refused to engage, her colleague Andrew Chael went public on Twitter, criticizing the awful and sexist remarks and attacks and emphasizing the significance of Bouman’s work on the team. One of the hate posters whose words are read out in the video characterized the episode as a “[...] tale as old as time. Men do all the work and prop up the whole industry but some woman comes along and all of a sudden [...] she takes all the credits, she gets all the fame. It never ends, folks, it never ends.” By comparing Lovelace’s and Bouman’s stories, Ditz’s work does not just contradict this proposition but turns it on its head, pointing out that little seems to have changed in almost two hundred years.

Cordula Ditz’s works are a summons to pierce the silence, to try to understand it so it can be broken. She uncovers the historic and intersectional structures underlying performative constructions of sex, gender, and identity by assembling their media manifestations in dense collages and montages that draw attention to the complex and unexpected undercurrents beneath the face of discrimination. Filtering stories from the mass media, our collective subsidiary memory, she enables us viewers to share in these experiences, creating an intellectual space in which solidarity and empathy can take root.